Проблемы этноконфессиональных групп

духоборцев и молокан

Светлана Иникова, РАН

|

Problems with [Spiritual Christian] Dukhobor

and Molokan Ethno-Denominational Groups

Svetlana A. Inikova, Russian Academy of Science

|

[A report on Spiritual Christians in the

Former

Soviet Union up to 1998. Russian copy at molokan.narod.ru/o/inikova01.pdf.

Edits in red text and images by Andrei Conovaloff, last

updated 14 March 2025. Edited text in square brackets for

photocopy visibility.]

Русский : М.Б. Олкотт и

А.В. Малашенко, Фактор етноконфессиональной самобытности

в постсоветском обществе — М., 1998. Стр. 84-104

English: M.B. Olcott and A.V.

Malashenko, ed. Fakto

etnokonfessional'noi samobytnosti v postsovetskom

obshchestvo (Original denominational factors in

post-Soviet society), Carnegie Endowment for International

Peace, Moscow. July 1998. 203 pages. Pages 84-104. ISBN

0-87003-140-6 Edited translation of L. Bliss, re-published

in Russian

Studies in History, vol. 46, no. 3, Winter

2007-8, pp. 78-96.

|

| Появление в России сект

духоборцев и молокан(1) (или духовных

христиан) можно отнести приблизительно к рубежу XVII-XVIII

вв. В основе молоканского и духоборческого учений лежали

идеи западного протестантизма (немецкого анабаптизма,

польского социнианства), а социальной базой сект стало

свободное крестьянство. В их учениях были идеи, подрывавшие

устои государства (непризнание божественного происхождения

верховной власти и земных законов, отказ от насилия вплоть

до отказа от защиты отечества, идея избранности и т. д.),

поэтому они всегда были гонимы — и в царское время, и потом

в советское. В начале XIX в. духоборцы и небольшая часть

молокан с разрешения правительства переселились и компактно

проживали в Таврии (Мелитопольский уезд) изолированно от

русского народа. Большая же часть молокан продолжала жить в

южно-русских и центральных губерниях среди православного

населения. В 1841-1845 гг. духоборцы были выселены в

административном порядке из Таврии в Закавказье. Туда же в

40-е годы началось добровольное массовое переселение молокан

из Тамбовской, Самарской и других губерний России. Они

основывали в Закавказье компактные поселения, главным

образом на территории современных Азербайджана и Армении,

хотя много молокан продолжало оставаться во внутренних

губерниях России. |

The Dukhobor and Molokan (or

Spiritual

Christian)

sects* emerged

in Russia around the end of the 1600s.(1) Their doctrines were founded on the

ideas of Western Protestantism (German Anabaptism,

Polish Socianism),

and

their social base was the free peasantry. Because their

doctrines included ideas that undermined secular authority

(the disavowal of the divine provenance of supreme power and

earthly laws; the repudiation of violence, up to and

including the refusal to defend the motherland; the idea of

elect status, etc.), they were constantly persecuted, both

under the tsars and later, in Soviet times. In the early

nineteenth century, the Dukhobory and a few Molokane

relocated, with government permission, to the Taurida

(Melitopol’skii district) [now south

Ukraine], where they lived in close proximity to

one another and in isolation from the Russian people [but friendly with

neighboring Germans, mostly Mennonites.]. But most Molokane continued

to live among the Orthodox in the provinces of southern and

central Russia. [Not so. See map below.]

In 1841–45 most they

were moved out of Taurida by administrative order and

resettled in the Transcaucasus, where Molokane also

voluntarily resettled in large numbers from Tambov and

Samara provinces and elsewhere during the 1840s. They

settled in compact colonies, mostly in what is now

Azerbaijan and Armenia, although many did continue to reside

in Russia’s interior provinces and

Taurida.

* Historically in Russia, "sect" simply meant "Russian" by

nationality but not Orthodox by faith. By law, citizens

(residents) of the Russian Empire who were not Muslims,

Jews, Buddhists or foreigners, were considered "Russian"

(a broad mixture of many nationalities) and must conform

to the state religion, else they are "heretics," criminals

who were often punished.

In the 1800s German immigrants in Russia were free to be

Lutheran, Catholic, Mennonite, Baptist, but not

neighboring Russian citizens who were not Muslim, Buddhist

or Jewish.

During the Soviet Union, most religion was outlawed,

except among the elderly.

For more detail see: N. A. Berdiaev. "Spiritual

Christianity and Sectarianism in Russia", (PDF),

Translator: Fr. S. Janos. "Dukhovnoe khristianstvo i

sectanstvo v Rossii," Russkaia Mysl’. November 1916. #252

____. “Tipy religioznoi mysli v Rossii”, Berdiaev

Collection (Tom III), pages 441-462. YMCA Press Paris,

1989.

The Russian terms for Dukhobor, Molokan and

Dukh-i-zhiznik as used here refer to broad

categories of surviving Spiritual Christian faiths, each

with major sub-divisions.

|

Map updated

from: The 1980 Молокан Directory, by A.J.

Conovaloff, (Clovis

CA) 1980, page 19. Data from History of Religious

Sectarianism in Russia (1860s - 1917),

by A.I. Klibanov, translated by Ethel Dunn,

1982, page 182; and original Russian: История

религиозного сектантства в России (60-е годы

XIX век-1917), page 147.

Most Spiritual Christian faiths (sects) are

not shown on this simplified. map. Most

Molokane (77%) never resided in the

Caucasus. "Siberia and the Far East" is mentioned

only once below, yet the Far East Molokane

(31%) were the most numerous and prosperous. (A.I. Klibanov, History of Religious

Sectarianism in Russia (1800s-1917),

translated by Ethel Dunn and Stephan P. Dunn,

1980.) Klibanov summarized 1909 census data, which

was displayed in Conovaloff, A.J.1980 Molokan

Directory, page 19, shown reorganized in

the map above. Not shown are the many Molokan

villages along river valleys in Siberia

between the Volga and Far East, and thousands who

remained in the south Ukraine.

Scholars concur that Russian censuses vastly

under-counted non-Orthodox Russians, who often

told officials they were Orthodox to avoid

arrest, or hid. Estimates for the actual total

census count of non-Doukhobor Spiritual Christians

could be be 2x,

3x, up to half a million or more. Though

the range of error remains debated, the

proportional distribution (%) among regions are

more likely to be representative, assuming that

under-reporting was proportionately consistent

across the Empire. From these estimates, it's

clear that less than 1% (~3000) of all non-Doukhobor

Spiritual Christians migrated to America in

the early 1900s, while about 35% (~8,800) of all Dukhobortsy

moved to Canada by 1930. (Researching

Your Russian Doukhobor Roots: A presentation by

Jonathan J. Kalmakoff, slide 30.) |

|

Поскольку в XVIII и XIX вв.

слово «православные» воспринималось как синоним слова

«русские», духоборцы и молокане, разорвавшие с православной

церковью, осознавали себя не русскими(2),

а особыми народами Божьими. Конфессиональные особенности

этих сект наложили сильный отпечаток на их культуру,

которая, несмотря на свою русскую основу, приобрела

существенные отличия от культуры их этноса. Осознание своей

культурной и религиозной особенности, богоизбранности,

общего исторического прошлого и позитивная

этноконфессиональная идентичность (высокая, если не сказать

завышенная, оценка «своего народа») в сочетании с негативным

восприятием культуры и религии русского народа и

соседей-кавказцев — все это являлось сущностью того

механизма, благодаря которому они консолидировались и смогли

на протяжении длительного времени существовать и сохранять

свою уникальную культуру.

|

Since in the 1700 and 1800s

the word “Orthodox” was taken to be synonymous with

“Russian,” the [Spiritual Christians]

Dukhobors and Molokans, having broken with

the Orthodox Church,

acknowledged themselves as non-Russians [sectarians, heretics, dissenters],

believing instead that they were God’s own special peoples.(2) The denominational idiosyncrasies of

the sects had a powerful impact on their culture, which,

despite its Russian foundations, came to differ

substantially from that of their ethnic origins. Their

awareness of cultural and religious distinction, their

status as God’s elect, their shared history, and their

positive ethno- denominational identity (their elevated, not

to say overstated, assessment of their “own people”),

combined with a negative perception of the culture and

religion of the Russian people and of their Caucasian

neighbors, formed the essential mechanism that knit them

together and enabled them to exist and maintain their unique

culture over the long term. |

Этот механизм начал

давать сбои еще на рубеже XIX в. В первые десятилетия

советской власти, которая провозгласила атеизм

государственной идеологией и использовала в борьбе с

религией все имевшиеся в ее распоряжении средства, процесс

его разрушения пошел значительно быстрее. С падением

религиозности и разрушением культурной обособленности

постепенно утрачивалась основа для консолидации. К середине

80-х годов представителей каждой их этих двух сект, и

верующих, и уже далеких от религии, объединяло самосознание,

в основе которого лежала не столько религиозная, сколько

культурно-историческая идея. Общины(3)

кавказских духоборцев и молокан объединяли еще и общность

территории и фактор иноэтничного окружения.

|

That mechanism began to fail

at the end of the 1800s. In the early decades of Soviet

power, which proclaimed atheism

the official ideology and employed all means at its

disposal to combat religion, the destruction of that

mechanism accelerated significantly. With the decline of

religious commitment and the dismantling of their cultural

insularity, the foundation of the sects’ cohesion was

gradually lost. Until the mid- 1980s, however, members of

both sects — both the faithful and those who held themselves

aloof from religion — were united by a self-awareness based

on an idea that was less religious than it was

culturo-historical.* The [isolated Spiritual Christian] Dukhobor

and Molokan communities in the Caucasus were also

united by a shared territory, surrounded by people of other

ethnicities .(3)

[*Zealous Dukh-i-zhizniki

insist they are united only by religion, their holy

books and current prophesy, because everything

"culturo-historical" is from man not God.]

|

| Все духоборцы и молокане,

прошедшие советскую школу, знали, что по национальности они

русские, тем не менее они гордились причастностью к своим

группам. Эта в целом позитивная этноконфессиональная

идентичность все же создавала некоторую дистанцированность

от русского народа. Вместе с тем позитивная идентичность

давала надежду, что в условиях либерализации политического

режима возможно возрождение этих русских сект. |

Although all [Spiritual Christians] Dukhobors

and Molokans who graduated from Soviet schools

knew that they were Russian nationals, they still took pride

in their group membership. That ethno- denominational

identification, although largely positive, distanced them

somewhat from the Russian people. Yet their positive self-

identification gave reason to hope that a liberalization of

the political regime might serve to revive [the Spiritual Christians] these

two Russian sects.

|

В конце 80-х лидерам

духоборческого и молоканского движений казалось, что

достаточно не на бумаге, а на деле дать людям свободу

совести, прекратить мелочный контроль со стороны

государства, и у них хватит собственных сил, желания и

энтузиазма возродить традиции, высокую нравственность,

привлечь тех, Проблемы этноконфессиональных групп духоборцев

и молокан кто, считая себя молоканами или духоборцами по

происхождению, отошел от религии и не принимал никакого

участия в духовной жизни общин.

|

In the late 1980s the leaders

of the two movements were convinced that if only freedom of

conscience were to be granted not on paper but in fact, and

if micromanagement by the state were to be halted, the [Spiritual Christians'] Dukhobors’

and Molokans’ own strengths, desire, and

enthusiasm would suffice to revive their traditions and

their high moral standards and to draw in those who

considered themselves [Spiritual

Christians] Dukhobors or Molokans

by origin but had abandoned religion and took no part in the

community’s spiritual life. |

| Этот подъем в среде

духоборцев и молокан совпал с развитием националистических

движений в Закавказье. Антирусская истерия, начавшаяся в

средствах массовой информации республик, расселение по

национальным квартирам стимулировало у кавказских молокан и

особенно у духоборцев быстрый рост этнического самосознания.

В сложных условиях межнациональных конфликтов им надо было

определиться, кто они. Начало 90-х годов характеризовалось

поиском новых идентичностей и массовыми переселениями

кавказских духоборцев и молокан на «историческую родину» в

Россию. Вместе с тем лидеры этих групп понимали, что

рассеивание переселенцев по стране среди русского населения

приведет к их быстрой ассимиляции, утрате наследия предков и

к еще большему ослаблению этих конфессий в целом, так как

наиболее крепкие общины были как раз в Закавказье. Массовое

переселение из Закавказья в Россию как бы подстегнуло,

ускорило процесс институализации этих сект, создание местных

и центральных представительных и руководящих органов,

призванных представлять их интересы на всех государственных

уровнях. |

This enthusiasm among [leaders of Spiritual Christians] Dukhobors

and Molokans coincided with the development of

the nationalist movement in the Transcaucasus. The

anti-Russian hysteria that began in the republics’ [Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan]

media and the ensuing national compartmentalization

stimulated a rapid growth of ethnic self-awareness among the

Molokans, and more particularly the Dukhobors, in the

Caucasus. At a complex time of conflict between nations,

they had to decide who they were. The early 1990s were

characterized by a search for new identities and by mass

migrations of [Spiritual Christians]

Dukhobors and Molokans of the Caucasus to

their “historical motherland” of Russia. Yet their leaders

realized that the dispersion of the settlers among the

Russian population countrywide would lead to their rapid

assimilation and the loss of the legacy left to them by

their forebears. It would serve to further weaken the

denominations as a whole, since the strongest of their

communities happened to have been in the Transcaucasus [segregated from

surrounding nationalities]. Furthermore, the mass

resettlement from the Transcaucasus to Russia impelled and

accelerated, as it were, the institutionalization of the

sects — the creation of representative and managerial

bodies, local and central, whose purpose was to represent

their interests at all official levels. |

Сейчас, почти десять лет

спустя, хорошо видны проблемы, которые надо было решить

духоборцам и молоканам, и то, в какой степени это удалось

сделать.

|

Now that almost a decade has

passed, we can clearly see the problems that the [Spiritual Christians] Dukhobors

and Molokans were set to resolve and the extent

to which they succeeded in doing so. |

| Чтобы возродить эти

религиозные группы, надо было остановить прямо-таки

катастрофическое падение их численности и омолодить состав,

поднять уровень конфессионального самосознания и

религиозности, надо было создать центральные органы и

выдвинуть лидеров, способных выработать программу и пути ее

реализации. |

To revive these

religious groups, it was necessary to stop the downright

catastrophic decline in their numbers and

rejuvenate composition,

raise the level of confessional identity

and religiosity,

and establish

a central authority and

nominate leaders who can

develop a program and ways to

implement it.

|

Сокращение числа верующих в

молоканских и духоборческих общинах началось еще в 30-е годы

и шло в нарастающем темпе. Для многих общин этот процесс

заканчивался самоликвидацией. Например, на Украине в

Мелитопольском уезде еще в 20-е годы в селе Астраханка было

семь молоканских общин и столько же молитвенных домов, в

селе Нововасильевка — пять общин и молитвенных домов. В

начале 90-х годов в этих селах было по одной общине. Такая

картина наблюдалась повсеместно. К началу 90-х годов в

большинстве молоканских общин даже в сельской местности было

по 15—60 человек, но было много и таких общин, которые

состояли всего из нескольких верующих.

. |

The numbers of the faithful [Spiritual Christians] in

Molokan and Dukhobor communities began to fall in

the 1930s, went rapidly downhill from there, and, in many

communities, culminated in self-dissolution. In the 1920s,

for instance, in Melitopol’skii

district, [south]

Ukraine [formerly

Tavria oblast, now in Zaparozhe oblast], the

village of Astrakhanka contained 7 Molokan congregations and

as many prayer houses, and the village of Novovasil’evka

had 5 congregations each with a prayer homes. [Novo-Spasskoe

had 3 congregations and churches. There were 15

congregations, each with a large building, plus a 2-story

Molokan religious educational and business center in

Astrakhanka. All buildings were still standing in 1992.

Only 3 are in use now for Molokan religious meetings.]

But in the early 1990s each village had only one Molokan

congregation*,

and that scenario was repeated everywhere. By then, most

Molokan communities, even in the countryside, had 15 to 60

members, but many consisted of only a handful of the

faithful.

[*After perestroika,

these Molokane wanted to repossess all 15 of

their religious buildings which were taken during Soviet

Collectivization. But the 2-story Molokan center

became the Astrakhanka civic center and police station,

some of the larger buildings were unsafe to occupy, and

others were used for storage, barns or community halls. They had to petition just

to get one per village. Since 2 generations grew up during

communism, few youth were taught religious rituals.]

|

The map above is

adapted from 2 maps created and copyrighted by Jonathan

Kalmakoff: "Doukhobors

in Russia, 1802"

and "Molochnaya

Doukhobor Settlement, 1802-1845". Kalmakoff states: "In Tavria

(present-day Zaporozhye province, Ukraine), the Doukhobors

settled along the [west side of the] Molochnaya River in

Melitopol district. The area was known as Molochnye Vody

(“Milky Waters”). There on the fertile steppe, they

planted grain fields and fruit orchards and established

nine villages as well as flour mills, textile mills, a

stud farm and extensive livestock herds. Their

landholdings totaled 131,417 acres [205 square

miles]." Molokans were given land on the east side

of the river taken from the local Nogai tribes,

just south of the very large German Molochna Colony, shown in

map below. For much more about the interaction among

non-Orthodox faiths in this territory see Russians'

Secret by Hoover and Petrov 1999; and Russia's

Lost

Reformation: Peasants, Millennialism, and Radical Sects

in Southern Russia and Ukraine, 1830-1917 by Zhuk

2004; and Heretics

and Colonizers: Forging Russia's Empire in the South

Caucasus by Breyfogle 2005 and his PhD thesis.

|

| Этот же процесс шел и среди

духоборцев. В самой многолюдной и крепкой духоборческой

общине села Гореловка в Грузии на моления собиралось по 20

человек и только в праздники их число увеличивалось до 50.

Это было связано с атеистическим воспитанием, с развитием

средств массовой информации и со стандартизацией культуры, с

оттоком молодежи в города и, конечно, с политикой

государства в отношении религиозных объединений, особенно

сект. В результате была нарушена преемственность поколений.

Численное сокращение религиозных общин и их старение вело к

тому, что регенерация духоборческой и молоканской культур не

могла происходить в полном объеме и на прежнем уровне. Их

культура утрачивала свою специфику |

The same process was under

way among the Dukhobors. Some twenty people gathered for

prayer in the largest and strongest Dukhobor community in

the village of Gorelovka, Republic of Georgia,

a number that only on holidays rose as high as 50. This was

brought about by official atheist indoctrination, by the

development of the mass media and cultural standardization,

by the outflow of young people to urban areas, and, of

course, by official policy on religious associations,

especially sects. As a result, the line of generational

continuity has been broken. The end result of the shrinking

and graying of religious communities was that the [Spiritual Christian] Dukhobor

and Molokan cultures could never be regenerated

fully or returned to their previous levels. Their respective

cultures had lost specificity. |

| Многие молоканские общины

из-за малочисленности прекращали регистрироваться и теряли

свой юридический статус, хотя он и немного значил в те годы.

Регистрацию обычно рассматривали как возможность сохранить

за общиной молитвенный дом. Собрания нелегально

существовавших общин проходили в частных домах, но

официально их уже как бы не существовало. К 1990 г. по всей

стране было зарегистрировано всего лишь менее полусотни

молоканских общин. Общины кавказских молокан, проживавшие в

сельской местности, вообще не считали нужным

регистрироваться, так как в селе они всегда могли найти дом

для собраний. Иногда колхоз выделял им помещение, а местная

администрация не обращала на это внимания, ограничивая

атеистическую работу рамками школы. |

Many Molokan communities

became too small to retain their registration and thus

forfeited their juridical status, which itself meant little

then except that it granted a community permission to

maintain its own prayer house, so that communities without

legal standing would have to meet in private homes. Those

communities no longer officially existed. By 1990 fewer than

50 Molokan communities were registered throughout the

country. [Dukh-i-zhiznik]

Molokan communities in the rural Caucasus

saw no need to register at all, since they could always find

a place to meet somewhere in the village. Sometimes the

collective farm would allocate premises for meetings,

restricting the teaching of atheism to the schools.

[In 2007, over 150 Spiritual Christian congregations were

meeting for Sunday services in the FSU, 60 in Stavropol'

territory. Most were on private property unrestricted by

the local authorities as long as they did not register as

a "church." Many Prygun congregations joined the

Union of

Congregations of Spiritual Christian Molokans (a

registered "church"), but Dukh-i-zhizniki did

not.]

|

Духоборцы никогда не

регистрировали свои религиозные объединения, и в 1988 г. на

запрос в Совет по делам религий о проживающих в Советском

Союзе духоборцах был получен ответ, что все они выехали в

Канаду в конце XIX в.

|

The Dukhobors never

registered; and in 1988 the Council on Religious Affairs,

having inquired how many Dukhobors were living in the Soviet

Union, was told that they had all emigrated to Canada in the

late nineteenth century. [About a 40% of all Doukhobors migrated to Canada by

1930.]

|

| Такое положение с

регистрацией вполне удовлетворяло и местные власти, так как

не портило картину религиозной ситуации, и самих сектантов,

поскольку им не надо было ни перед кем отчитываться, да и

деятельность их сводилась к молитвенным собраниям и

поддержанию в порядке культовых мест. Никакой общественной,

а тем более миссионерской деятельности они не вели, так как

это было просто невозможно. |

The registration situation

was entirely satisfactory — both to the local authorities,

since it did not mar the picture of the religious status

quo, and to the sectarians themselves, because it meant they

did not have to account to anyone, especially since their

activities amounted only to attendance at prayer meetings

and the upkeep of their places of worship. They were not

active socially and certainly did not proselytize, because

they could not even if they had wanted to.

[There seems to be no restrictions for Orthodox joining

Molokans. In 1992 in Tselinskii

raion, Rostov Oblast, many Orthodox women

joined the largest Molokan congregation, and the

head singer was a sister of the local Orthodox priest.]

|

| Чтобы начать деятельность по

возрождению молоканства и духоборчества, надо было прежде

всего создать руководящие органы. Духоборцы и молокане в

СССР не имели центральных организаций. Еще до революции

после некоторой либерализации законов в 1904-1905 гг.

молокане неоднократно пытались объединиться и создать

организационные структуры, созывали съезды, но реального

объединения разобщенных молоканских общин Закавказья, Южной

и Центральной России, не говоря уже о Сибири и Дальнем

Востоке, не произошло. |

As a first step in reviving [Spiritual Christianity] Molokanism

and Dukhoborism, managerial bodies would have to

be created, because neither group had any central

organizations in the USSR. Even before the Revolution, when

the laws were somewhat liberalized in 1904 and 1905, the

Molokans attempted on several occasions to unify, to fashion

organizational structures, to convene congresses, but there

was never any real unification of the scattered Molokan

communities in the Transcaucasus and southern and central

Russia, not to mention those in Siberia and the Far East.

[About 1905 Molokane built 2-story educational

centers in Tiblisi (Georgia), Baku (Azerbaijan) and

Astrakhanka (Ukraine), and in San Francisco (USA) in 1929.

In Los Angeles (USA) in 1926, an integrated organization

of mixed Spiritual Christians formed the UMCA — United

Molokan Christian Association, now controlled by Dukh-i-zhizniki.

Today only the divided organizations in the USA exist.]

|

| Духоборцы до конца XIX в.

подчинялись своим духовным вождям, возведенным в ранг

«христов» (или «богородице») и решению съездов

представителей всех сел, расположенных в Закавказье и

Карсской области. Неоднократные расколы и переселения в

конце XIX в. — начале XX в. сильно подорвали единство секты

и ослабили ее. Репрессии, начавшиеся в конце 20-х и

продолжавшиеся до конца 30-х годов, вырвали из рядов

духоборцев самых убежденных и авторитетных людей, и всякие

попытки организоваться были подавлены в зародыше. |

Up to the end of the 1800s,

the Dukhobors had subordinated themselves to their spiritual

leadership, whom they elevated to the rank of “Christs” (or

[if female], “Mothers of God”)

and to the decisions taken by congresses of representatives

from all the villages in the Transcaucasus and Kars oblast.

Recurrent schisms and resettlements in the late 1800s and

the early 1900s severely undermined the sect’s unity and

weakened it; the repressions that began in the late 1920s

and continued until the end of the 1930s wrested away the

most committed and authoritative Dukhobors; and any attempts

to organize were nipped in the bud. |

|

[In 1990, Aleksandrov

joined the Committee for Relations with Religious

Organizations (CRRO) in Moscow, filed to register the Molokan

faith, got a grant to hold an organizational meeting,

reserved a banquet hall, announced the meeting on Radio

Moscow broadcasted to nearly all households in the

country, not knowing if any practicing Molokane were

listening. He was astonished by the response.] |

| В течение 90-х годов в целях

объединения духоборцы и молокане провели ряд съездов. Для

подготовки первого молоканского съезда И. Александров в 1990

г. начал издавать возрожденный журнал «Духовный христианин»,

в котором печатались подготовительные материалы. Весной 1991

г. в разных регионах страны начали создаваться союзы общин

или комитеты духовных христиан-молокан данного региона во

главе со старшим пресвитером или председателем. Оргкомитет

по подготовке съезда в апреле того же года начал выпускать

информационный листок «Весть», с помощью которого собирался

информировать общины о ходе подготовки съезда. Незадолго до

съезда была создана благотворительная ассоциация «Община»,

декларированной целью которой было «возрождение

молоканства». Инициатором ее создания, как и созыва съезда,

стал И. Александров, сыгравший большую положительную и столь

же отрицательную роль в молоканском движении. |

The [Spiritual

Christians] Dukhobors and Molokans

held a number of congresses in the 1990s, with a view to

unification. In 1990, to prepare for the first Molokan

Congress, Ivan Aleksandrov revived the periodical Dukhovnyi khristianin

and used it to publish preparatory

materials. In the spring of 1991 in various regions of the

country, local community unions or committees of Spiritual

Christian Molokane, headed by the senior presbyter

or president, were being set up. In April of that year, an

organizing committee began issuing a fact sheet titled Vest’, which was

intended to inform the communities of progress made in

planning the congress. Not long before the congress was

convened, the Obshchina [Community]

charitable association was set up with the declared goal of

“reviving Molokanism.” This was done at the initiative of

Aleksandrov, who had set up the congress. He was a major

player in the Molokan movement, although he ultimately did

it about as much harm as good.

|

|

[Aleksandrov's leadership

was attacked mainly because he led a minority who

envisioned a central office in Moscow, where most business

in Russia is centrally managed. Also, he was not raised in the faith, his Azeri

wife and 2 boys did not participate, and the founding

Moscow organization did not manage records well.

The most vocal opponent was refugee V.V.

Schetinkin, an upstart presbyter from Khimili,

Azerbaijan, who lobbied for a southern center in his

village of Kochubeevskoe, Stavropol, near thousands of

other refugees, also from North rural Azerbaijan.

Also in 1990, an

American Dukh-i-zhiznik presbyter, Vasili Sissoyev

in Montebello, California, was frustrated that he could

not get a visa to Russia. His wife suggested he

complain to Yeltsin. His letter was redirected to the

CRRO, and placed in the Molokan box. Aleksandrov

requested his visa which was approved. Sissoyev, attended and video

taped much of the 1991 Convention, which was shown to many

in the U.S.A.

In 1992, about 30 diaspora non-Doukhobor Spiritual

Christians attended the 2nd Annual Congress held in

Astrakhanka,

Zaporizhzhia

Oblast, (Астраханка, Zaporizhia Oblast) Ukraine. No

diaspora returned in numbers until the 2005 when about 10

Molokane from the San

Francisco congregation attended the 200th Anniversary.

Since 1992, Dukh-i-zhiznik have

not formally affiliated with Molokane.]

|

| Первый

съезд духовных христиан состоялся в Москве в июне

1991 г. На съезд приехали представители более 60

общин, а членами созданного Союза общин духовных

христиан-молокан СССР стали более 40 общин.

Некоторые вступали единолично. Знаменательно, что

Союз был открыт для всех течений молоканства. Он

должен был возродить молоканство и связать

разрозненные общины всех направлений. Однако на деле

членами его стали только постоянные молокане. На

съезде был принят Устав, а в старшие пресвитеры

рукоположен И. Александров. |

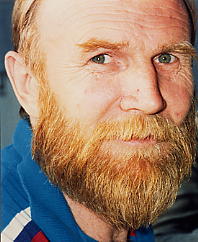

Ivan G. Aleksandrov, 1992

И. Г. Александров

|

The first

Congress of Spiritual Christians [Molokane] took

place in Moscow in June 1991. It was attended by

representatives from more than sixty communities,

and over forty communities came together to form the

new Union of Communities of Spiritual Christian

Molokans of the USSR [UCSCM]. Some people also

joined the union as individuals. Although it is

indicative that the union was open to all the

various [non-Doukhobor

Spiritual Christian] Molokan

groups, its intent being to revive [Biblical Spiritual Christianity]

Molokanism and link the

disconnected communities, whatever their persuasion,

in fact only Constant Molokans

joined. The congress adopted a charter and ordained

Aleksandrov as senior presbyter. [By 2014, no Dukh-i-zhiznik

congregations joined.] |

|

[Многие

духовные христиане были переселены из

Карса, Турции, в Ростовской

области в 1926 году,

и поделили

между двумя колхозов.] |

[Many Spiritual Christians were

relocated from Kars, Turkey, to east Rostov province in

1926, and divided among two collective farms. In 1992 only

1 Prygun congregation existed in Tselinskii

raion. After 2000, at least 3 Dukh-i-zhiznik congregations

resettled nearby from Amenia, 2 to the north and one to

the south of the mapped area.]

|

Следом за молоканским съездом

с разрывом в две недели в Целинском районе Ростовской

области состоялся Всесоюзный съезд духоборцев. Накануне его

созыва в Целинском районе, где проживают духоборцы,

переселившиеся туда еще в 1921-1923 гг., уже было

зарегистрировано «Религиозное объединение духовных борцов

Христа в СССР». Инициатором регистрации и одним из главных

инициаторов созыва съезда стал Ю. Крыжановский, человек,

далекий от какой-либо веры, преследовавший личные корыстные

интересы и в дальнейшем принесший духоборческому движению

много неприятностей и разочарований.

|

Only two weeks after the

Molokan Congress ended, an All-Union Congress of Dukhobors

opened in Tselinskii

raion, Rostov oblast, which was inhabited by Dukhobors

who had resettled there in 1921–23. Immediately before the

meeting, the Religious Alliance of Spiritual Warriors [(Wrestlers, Fighters)] of Christ

in the USSR was registered, at the initiative of Iurii

Kryzhanovskii, who had also been instrumental in arranging

the [Dukhobor] Congress. Kryzhanovskii, a

person far from devout in any faith, was pursuing his own

selfish interests and was later to cause a great deal of

unpleasantness and disappointment for the Dukhobor movement.

|

Iurii Kryzhanovskii and wife, 1992

Ю. Крыжановский

|

[Kryzhanovskii and wife in October 1992, while

visiting the administrator of Chern' district, Tula

province. He is a retired army general, with Communist

Party ties and negotiating skills, unlike that of the

worker class Doukhobors whom he adopted to govern. He was

one of thousands of former high ranking ex-Soviets struggling to

professionally reposition themselves to maintain economic status

during the chaos of perestroika.

Because his ancestry was Doukhobor, he chose to appoint

himself leader of the Doukhobors though he did not adhere

to the Doukhobor faith. Many Canadian Doukhobors consider

him to be an opportunist who exploited their Russian

brethren.] |

| В свидетельстве о регистрации

Ю. Крыжановский определил вероисповедную принадлежность

духоборцев следующим образом: «Православная христианская

этническая группа раскольников». Однако поскольку

религиозное объединение было уже зарегистрировано, с тем

духоборцы и пришли к всесоюзному съезду. Он вылился в

большое собрание наподобие партийных; делегатов на съезде

было немного. Обсудили современные методы повышения

продуктивности земли и развитие малых предприятий по

переработке сельхозпродукции, затем решали организационные

вопросы. Никакие сугубо духоборческие, а тем более духовные

проблемы не поднимались. Положительным было то, что съезд

дал толчок поиску путей объединения духоборцев, и на нем был

избран Совет духоборцев СССР из 15 человек. Он должен был

руководить между съездами, а для организации переселения и

связи с государственными структурами был избран исполком.

Съезд обратился ко всем духоборцам страны с призывом «более

активно возрождать традиции, нравы, обычаи, обряды

духоборцев». Всем духоборцам съезд рекомендовал

«использовать все возможности для возрождения и создания

духоборческих общин и других форм, наиболее подходящих для

совместной работы и безбедной, зажиточной жизни». |

On the registration

certificate, Kryzhanovskii defined the Dukhobors’ religious

affiliation as an “Orthodox Christian ethnic group of

schismatics.”* The Dukhobors

arrived at the all-union congress under that designation,

the registration being by then a done deal. But the congress

resembled nothing so much as a glorified party meeting,

since few delegates attended and the first matters up for

discussion included modern methods of increasing land

productivity and the development of small enterprises to

process agricultural output. Only after that were

organizational issues tackled. No expressly Dukhobor, or

even spiritual, problems came up. The congress’s only

positive result was that it set in motion a search for ways

of uniting the Dukhobors and elected a 15-member Dukhobor

Council, whose mission was to provide leadership between

congresses, and an executive committee to organize

re-settlements and establish liaisons with state structures.

The congress appealed to all the country’s Dukhobors with a

call to “be more active in reviving the traditions, mores,

customs, and rituals of the Dukhobors” and advised all

Dukhobors “to employ every opportunity to revive and create

Dukhobor communities and other forms most fitting to

cooperative work and a life of comfort and affluence.”

[* This is a definition of Old

Believers, Old

Ritualists, not Spiritual Christians.]

|

| Для того, чтобы отмежеваться

от Ю. Крыжановского и создать крепкую, поддерживаемую всеми

духоборцами организацию, летом 1992 г. в селе Архангельское

Чернского района Тульской области, куда в 1989-1991 гг.

переселилась часть кавказских духоборцев, был созван второй чрезвычайный

съезд. Он оказался более многолюдным и представительным, чем

первый. На нем был принят устав и решено перерегистрировать

духоборческую организацию под новым названием — «Объединение

духоборцев России», так как после распада Советского Союза

прежнее название уже не отражало действительной ситуации. В

уставе было оговорено, что в Объединение на равных могут

входить духоборческие общины из СНГ. |

To dissociate from

Kryzhanovskii and form a strong organization that would have

the support of all Dukhobors, a second, extraordinary

congress met in the summer of 1992 in the village of Arkhangel’skoe,

Chernskii raion, Tula oblast,

where Dukhobors from the Caucasus had resettled in 1989–91.* This congress was

better attended and more representative than the first. It

adopted a charter and resolved to re-register the Dukhobor

organization under a new title — Alliance of Dukhobors of

Russia — since the old name no longer reflected the

situation that obtained after the collapse of the Soviet

Union. The charter stipulated that all Dukhobor communities

in the Commonwealth

of Independent States (CIS) could join as equals.

|

|

[* These

Doukhobors would resettle only if given their own land,

with their own farm administrator. The Chern' district

administrator who flew to Georgia to recruit Russian

farmers divided his largest collective farm [kolkhoz],

and

gave

about half to the Doukhobors who called it the "L.N.

Tolstoy Settlers Dukhobor Collective Farm/Community." This

was a significant reversal of history, because nearby,

across a creek to the west (19 km., 12 mi. walking), the

old estate

of Sergei Lev. Tolsoy was being restored as a

museum. Doukhobor

serfs lived there 200 years ago. L.N. Tolstoy lobbied for

their freedom, paid for about a fourth of their migration,

and his son Sergei accompanied the first boat of

Doukhobors to Canada with other aides. Now many descendants have

returned to their rural Russian homeland.] |

| Центральные органы

молоканского и духоборческого объединений сразу же взялись

за решение переселенческого вопроса. Уже в ноябре 1991 г.

совет Союза общин ДХМ постановил создать Комитет содействия

переселенцам-молоканам. Этот комитет искал земли для

переселения общин из СНГ, чтобы сохранить их и тем самым

возродить молоканскую культуру на новом месте. Союз общин

ДХМ обращался в высшие инстанции вплоть до президента с

просьбой о помощи переселенцам. Совет Союза составлял

необходимую документацию, сметы, проект будущего поселения.

Он добился выделения для переселенцев земель в Чернском

районе Тульской области. |

The central organs of the [Spiritual Christian] Dukhobor

and Molokan unions promptly took up the

resettlement issue. As early as November 1991 the UCSCM had

resolved to set up a Committee to Assist Molokan Settlers [Komitet sodeistviia

pereselentsam-molokanam], which searched for land

to be settled by communities from the CIS, so as to preserve

them and to regenerate the Molokan culture in a new

location. The UCSCM appealed all the way up to the

president [Yeltsin] to elicit

help for the settlers.* Its

council had compiled a small package of documentation

containing estimates and the plan for a future settlement,

and it was eventually allocated lands for resettlement in

Chernskii raion, Tula oblast.

[* In 1990, Aleksandrov joined the Committee for Relations

with Religious Organizations in Moscow, filed to register

the Molokan faith, got a grant to hold an organizational

meeting, reserved a banquet hall, announced meeting on

public radio (Channel 1) to nearly all households in the

country, and was astonished by the turnout.] |

Созданный на первом

духоборческом съезде исполком по переселению со своей

миссией не справился. Была сделана попытка создать внутри

совета специальный комитет по переселению, но он тоже

оказался неработоспособным, и его функции взял на себя совет

Объединения духоборцев России, который выступал в качестве

юридического лица от имени переселенцев.

|

The executive committee for

resettlement formed at the first Dukhobor Congress was,

however, never equal to its mission. A special committee on

resettlement that was established within the executive

committee also proved ineffectual, and its functions were

assumed by the ADR Council, as the legal entity representing

the settlers. |

| Деятельность центральных

органов и реализация программ по возрождению молоканства и

духоборчества были невозможны без материальных средств. И.

Александров с самого начала объединительного молоканского

движения выдвигал вопрос о создании предприятий, средства от

которых пошли бы на помощь переселенцам из Закавказья, на

финансирование журнала, содержание редакции и на необходимые

организационные расходы Союза общин ДХМ. Ассоциация «Община»

как раз и должна была объединить руководителей молоканских

колхозов и кооперативов, но она оказалась мертворожденной. В

проекте устава будущего Союза общин ДХМ говорилось, что Союз

не только будет способствовать развитию «чувств самосознания

в правовом и общественном отношении» и т. п., но и берет на

себя посредничество между земледельцами, куплю и продажу

машин и оборудования, земли, семян, скота и других

необходимых товаров, предоставление кредитов. Средства Союза

должны были складываться из членских взносов и добровольных

пожертвований. Но уже на стадии его обсуждения были

серьезные нарекания с мест, что это устав не духовных, а

«плотских христиан-молокан». В Устав,

принятый на съезде, пункт об обязательных членских взносах

включен не был, но все же остались положения об

экономической деятельности Союза общин ДХМ

(внешнеэкономическая деятельность, производство и реализация

сельхозпродукции, открытие магазинов и лавочек и т.д.). |

Without material resources,

the central bodies could not act, and the programs to revive

[Spiritual Christianity] Dukhoborism

and Molokanism could not be implemented. From the

beginning of the movement for Molokan movement, Aleksandrov

had urged the setup of commercial enterprises to generate

funds that would help those resettling from the

Transcaucasus, finance a periodical, compensate its

editorial board, and defray the UCSCM’s necessary

organizational expenditures. (The Obshchina association

was actually supposed to have united the leaders of Molokan

collective farms and cooperatives, but it had been

stillborn.) The draft charter for the future UCSCM had

stated that the union would not only facilitate the

development “of legal and social self-awareness” and so on

but would also broker agreements among farmers; arrange the

purchase and sale of machinery and equipment, land, seed,

livestock, and other necessities; and extend credit. The

UCSCM’s financial resources were to come from membership

dues and voluntary donations, but while its charter was

still in the discussion stage, there were serious complaints

from the localities that it catered not to Spiritual

Christian Molokans but to “carnal Christian Molokans.”* So a paragraph on mandatory

membership dues was omitted from the Charter adopted at the

congress, but provisions regarding the economic activity of

the UCSCM (foreign trade, the production and sale of

agricultural products, the opening of stores and stalls,

etc.) remained.

[* Molokans in name only, not faith.

Canadian Doukhobors use the term: "Doukhobors in name

only" to indicate descendants who no longer attend

meetings, inter-married, and have abandoned the Doukhobor

faith, principles, lifestyle or movement — assimilated.]

|

| Вопрос об обязательных сборах

не утратил актуальности до сего дня. На страницах журнала

«Слово веры» последние годы развернулась широкая полемика по

этому вопросу. Для молоканских пресвитеров и активистов

движения оказалось важнее остаться вне каких-либо подозрений

в корысти и избежать возможных упреков в том, что они служат

«ради обогащения или даже ради легкой добычи хлеба

насущного»(4), чем создать

экономическую базу для дальнейшей работы Союза общин ДХМ. |

The issue of mandatory fees

is being debated to this day; in recent years, the magazine

Slovo very has

carried an extensive and heated exchange on the subject.

Molokan presbyters and movement activists have found it more

important to remain free of any suspicion of greed and to

avoid possible accusations of serving “for the sake of

enrichment and even for an easy way to procure their daily

bread” than to create an economic base that the UCSCM could

use going forward.(4) |

| Духоборцы и молокане в силу

своих религиозных установок не знали, что такое десятина в

пользу их церкви, оплата труда пресвитера или кого-то из

старцев, певчих. Добровольные пожертвования всегда делались

так, чтобы никто не видел, кто сколько жертвует.

Материальное, земное вторгалось в духовную жизнь, но одни не

хотели считаться с требованиями времени, а другие не знали,

как совместить то и другое. Это противоречие между традицией

и назревшей необходимостью так и не удалось преодолеть. |

The religious tenets of the [Spiritual Christians] Dukhobors

and Molokans did not include tithing to the [congregation] church

or compensating the presbyter, elders, or singers for their

work. Voluntary donations were always made in secret [under a towel on the alter

table], each giving what he or she could afford.

Material reality was now invading the life of the spirit,

but some did not want to accommodate the demands of the time

and others did not know how to merge the two. The

contradiction between tradition and looming [financial] necessity has never

been successfully overcome. |

| К сожалению, в начале 90-х

молокане передоверили свои материальные проблемы И.

Александрову, а ростовские духоборцы — Ю. Крыжановскому. На

бумаге за подписью последнего вырастали несуществующие

«Генеральное строящееся предприятие» и «Комитет по

переселению духоборцев в Ростовскую область». Начались аферы

со средствами, выделенными Комитету опять же в лице Ю.

Крыжановского. Нарекания в нарушении финансовой дисциплины

были со стороны молокан и в адрес И. Александрова.

Безусловно, подобные факты дискредитировала саму идею

экономической деятельности молоканских и духоборческих

организаций. |

In the early 1990s,

unfortunately, the Molokans had entrusted their material

problems to Ivan Aleksandrov, and the Rostov Dukhobors had

delegated theirs to Iurii Kryzhanovskii. A General

Construction Enterprise and a Committee to Resettle

Dukhobors in Rostov oblast, neither of which actually

existed, sprang up on paper, above Kryzhanovskii’s

signature. Shady deals were put together using funds

allocated to the committee, again as represented by

Kryzhanovskii. The Molokans began accusing Aleksandrov of

financial irregularities. Facts such as these unquestionably

discredited the very idea of the economic activities being

conducted by the [Spiritual

Christian] Molokan and Dukhobor

organizations. |

| Острый недостаток средств

значительно затруднил и продолжает затруднять

организационную работу. Рассчитывать на систематическое

поступление пожертвований не приходится, так как подавляющее

большинство верующих — пенсионеры, т. е. люди

несостоятельные, зачастую просто нищие. Американские и

австралийские молокане и канадские духоборцы периодически

помогали своим российским единоверцам, но эти субсидии,

зачастую предоставляемые в виде гуманитарной помощи вещами и

продуктами, не решали проблему. Правда, американские и

австралийские молокане выделяли средства на организацию

съездов, на издание журналов, строительство молитвенного

дома в Ставропольском крае, но сами они не богаты, и эта

помощь не идет ни в какое сравнение с солидными вливаниями,

которые делают зарубежные адвентистская или баптистская

церкви своим единоверцам. |

Organizational efforts were,

and continue to be, significantly complicated by an acute

shortage of funds. The sects could not rely on a systematic

receipt of donations, since the overwhelming majority of the

faithful consisted of senior citizens who had limited means

and were often simply impoverished. American and Australian

Molokans* and

Canadian Dukhobors have periodically sent help to their

Russian coreligionists, but such subsidies, which often take

the form of humanitarian aid (food and nonfood items), have

not resolved the problem. The American and Australian [non-Doukhobor Spiritual Christians]

Molokans have

allocated funds for congresses*, the publication of periodicals, and the

construction of a prayer house[s]

in Stavropol krai, but they themselves are not rich, and

their assistance pales in comparison with the considerable

infusions of cash sent by foreign Adventist or Baptist

churches to their own coreligionists.

[* Initially diaspora non-Doukhobor Spiritual Christians

joined in fund-raising and collection of

humanitarian aid, but by 1995 the more numerous diaspora Dukh-i-zhizniki

primarily donated to 3 Dukh-i-zhiznik

congregations in Stavropol' province, rather randomly

selected as pet projects by different presbyters in

California, to the dismay of neighboring Dukh-i-zhiznik congregations

who got no aid. An anomaly is a lone Prygun congregation

in Levokumskoe, Stavropol' province, which was funded to

build the "largest meeting hall in Russia" by American

businessman William M. Shubin, Fresno, who naively thought

most Dukh-i-zhizniki would

flock to the largest assembly hall, without considering

location, denomination and transportation.]

|

Деятельность молоканских и

духоборческих в прошлом колхозов, ныне получивших статус

«общин» и «товариществ», не является экономической

деятельностью религиозных организаций. Если они что-то и

выделяют религиозным общинам или центральным организациям,

то это не обязательный взнос, а добровольная помощь, причем

чаще всего направленная на поддержку культурных инициатив.

Например, небольшие средства время от времени выделял в

распоряжение Совета духоборцев переселенческий духоборческий

колхоз — община им. Л. Н. Толстого в Тульской области. На

эти деньги была выпущена пластинка с записью духоборческих

псалмов и народных песен, издано несколько номеров газеты

«Вестник духоборцев».

|

The entities that used to be

[Spiritual Christian] Molokan

and Dukhobor collective farms and are now

accorded the status of “communities” and “partnerships” do

not operate economically as religious organizations. If they

allocate anything to the religious communities or to central

organizations, they do so not as mandatory dues but as

voluntary assistance, which is more often than not earmarked

to support cultural initiatives. For example, the L.N.

Tolstoy Settlers Dukhobor Collective Farm/Community in Tula

oblast has from time to time placed small sums at the

disposal of the Dukhobor Council, which moneys were used to

make and release a commercial recording of Dukhobor psalms

and folk songs and to publish several issues of the Vestnik dukhobortsev. [The large Molokan-owned and managed Nikitin collective farm

in Ivanovka, Azerbaidjan, has uniquely survived since

Soviet times, though many have moved to Russia. At least

200 families from Ivanovka now live in Moscow with no

large meeting hall.]

|

| В 90-е годы была предпринята

попытка ведения экономической деятельности духовной

молоканской общиной. Во время строительства молитвенного

дома в селе Кочубеевское

Ставропольского края молоканская религиозная община

организовала производство кирпича и открыла цех по

производству оконных рам и дверей и часть продукции

продавала. Также был открыт маленький пошивочный цех,

благодаря которому несколько женщин-молоканок получили

работу, а прибыль от него шла на строительство того же дома. |

One Molokan spiritual

community did make a stab at for-profit activity in the

1990s. While building a prayer house in the village of Kochubeevskoe,

Stavropol territory, the Molokan religious community set up

a brickworks and a workshop to produce window frames and

doors and sold a portion of the output. A small sewing shop

was also opened, which provided work to some Molokan women,

with the profits going to the building project. [These enterprises were

funded via the Molokan Liaison Committee, San Francisco, which

also supported building the large Kochubeevskoe

prayer hall. Support for the committee failed before

2000 and soon after the businesses shut down. The wood

shop was converted to a dormitory for guests during the

2005 Anniversary, and the brick shop is now a new 3-room

museum with 2 rooms depicting their former rural- hut

lifestyle.]

|

| После первых съездов в

общинах чувствовался подъем. С целью объединения

представители совета Союза общин ДХМ ездили по общинам

России и СНГ. В начале 90-х годов совет Союза помогал

общинам добиваться возвращения молитвенных домов,

распределял по общинам литературу и гуманитарную помощь.

Активную деятельность вел совет Объединения духоборцев

России, который собирался три раза в год на территории общин

Ростовской и Тульской областей, Северного Кавказа, Грузии.

Однако, подводя итоги деятельности этих организаций,

приходится признать, что их объединительная миссия не

принесла ожидаемых плодов. Центробежные силы оказались

намного сильнее, чем можно было ожидать. Мигрирующие из

Закавказья духоборцы и молокане, несмотря на заявления о

желании поселиться в России компактными группами и сохранить

свою культуру, в подавляющем большинстве разъехались по

стране. Непреодолимым препятствием на пути к единству

оказалась борьба за лидерство внутри сект и вместе с тем

недоверие к избранным лидерам. В основе этого явления, на

наш взгляд, помимо присущих всем людям слабостей, лежит

характерное для молокан (а с конца XIX в. и для духоборцев)

непризнание иерархического устройства духовной общины(5). Отчасти настороженное отношение

духоборцев и молокан к собственным лидерам можно объяснить

еще и печальным опытом начала 90-х годов. |

The first congresses brought

a sense of uplift to the communities. UCSCM representatives

visited communities in Russia and the CIS, with the goal of

effecting Molokan unity. In the early 1990s the UCSCM

Council assisted communities in their efforts to regain the

use of their prayer houses and distributed literature and

humanitarian aid. The ADR Council was also active, meeting

three times a year within the ambit of the communities of

Rostov and Tula oblasts, the North Caucasus, and the

Republic of Georgia. After tallying everything those

organizations did, however, it must be acknowledged that

their mission of unification did not yield the expected

fruits, because the centrifugal forces were far stronger

than had been anticipated. The overwhelming majority of [Spiritual Christians] Dukhobors

and Molokans who migrated from the Caucasus were

dispersed throughout the country, despite their declared

desire to resettle in tight-knit groups in Russia and thus

preserve their culture. An insuperable obstacle on the path

to unity was the sects’ internal power struggle, accompanied

by mistrust in their elected leaders. This phenomenon had

its foundation in something other than the weaknesses

inherent in us all. In our view, it rested on the disavowal

characteristic among Molokans (and Dukhobors from the late

1800s onward) of any hierarchical structure within the

spiritual community.(5) Such wariness

on the part of [Spiritual Christians]

Dukhobors and Molokans toward their own

leaders may also be explained in part by their dismal

experiences of the early 1990s. |

| Осенью 1991 г. И. Александров

отказался от должности старшего пресвитера и занял пост

председателя совета Союза общин ДХМ. В сентябре 1993 г. было

проведено два съезда: один — в селе Кочубеевском

сторонниками старшего пресвитера Т. Щетинкина, другой — в

Москве сторонниками И. Александрова. В 1994 г. И.

Александров был окончательно отстранен от руководства

Союзом. Хотя перерегистрированный 6 декабря 1994 г. с новым

названием Союз общин ДХМ России продолжал существовать,

восстановить прежнее единство не удалось. Последний съезд,

проходивший в Тамбове в августе 1997 г., был созван не

советом организации, а лидерами тамбовских молокан и был

проигнорирован рядом общин, тяготеющих к объединению вокруг

Т. Щетинкина и создаваемого им молоканского центра в селе

Кочубеевском. В сентябре того же года Т. Щетинкин от имени

совета Союза общин ДХМ тоже собрал представителей некоторых

общин на «домообновление» (освящение молитвенного дома)

Центрального дома молитвы Союза общин ДХМ России, которое

должно было по мысли устроителей вылиться в съезд. |

In the fall of 1991

Aleksandrov resigned as senior presbyter, assuming instead

the post of UCSCM president. Two congresses were held in

September 1993, one in the village of Kochubeevskoe by

supporters of Senior Presbyter Timofei Shchetinkin and the

other in Moscow by Aleksandrov’s followers. In 1994

Aleksandrov was ousted from the UCSCM leadership. Although

the UCSCM re-registered on 6 December 1994 under a new name,

the prior unity could never be restored. The last congress,

held in Tambov in August

1997, was called not by the UCSCM Council but by the

leaders of the Tambov Molokans and was ignored by the

numerous communities that were beginning to coalesce around

Shchetinkin and the Molokan center that he had created in

Kochubeevskoe. In September 1997 Shchetinkin also summoned,

in the name of the UCSCM Council, representatives from

several communities to attend the dedication of the UCSCM’s

Central Prayer House, a gathering that the organizers

intended to turn into a congress. |

| Процесс

распада Союза общин ДХМ хорошо виден на примере

издания журналов. С 1990 г. по 1994 г. в Москве под

редакцией И. Александрова выходил общемолоканский

журнал «Духовный

христианин», а с 1991 г. — журнал «Весть»,

издававшийся более четырех лет также в Москве. Оба

издания были органами Союза. В 1994 г. в Москве был

основан другой журнал — «Слово веры».

Он мыслился как центральный и независимый от Союза

общин ДХМ орган, целью которого была только

проповедь Евангелия. В 1997 г. журнал с одноименным

названием без согласования с редакцией «Слова веры»

выпустила община села Кочубеевского. После этого

московский журнал с девятого номера был переименован

в «Доброго

домостроителя благодати». В 1997 г. в поселке

Слободка Чернского района Тульской области пресвитер

молоканской переселенческой общины В. Тикунов

выпустил два номера журнала «Млечный путь»

литературно-исторического направления. |

[By 2007,

Viktor Tikubnov and wife Tania (no kids) moved to

Moscow where he found a part-time job in a

bookstore, and launched a new website: По Следам

Молоканства (On the Molokan Trail). E-mail:

Tikunov.Viktor@itrm.ru].

In July 2008 his congregation in Tula province

hosted a youth

conference.

|

The

publication of Molokan periodicals readily

illustrates the process of the UCSCM’s dissolution.

From 1990 through 1994 the Molokan magazine Dukhovnyi

khristianin was published in Moscow,

with Aleksandrov as editor; the magazine Vest’ was

published for over four years beginning in 1991,

also in Moscow. Both were UCSCM publications. In

1994 another magazine — Slovo very

— was founded in Moscow, as a central organ

independent from the UCSCM, with the sole goal of

preaching the Gospel. In 1997 the Kochubeevskoe

community began publishing a periodical of the same

name, without the approval of the editorial board of

the original Slovo

very. So the Moscow magazine, beginning

with its ninth issue, was renamed Dobryi domostroitel’

blagodati. Also in 1997 two issues of

a generally literary/historical magazine entitled Mlechnyi put’

were published in the settlement of Slobodka,

Chernskii raion, Tula oblast, by Viktor Tikunov,

presbyter of the Molokan community that had

resettled there. |

|

| Совет Объединения духоборцев

России постепенно превратился в организацию, представляющую

интересы духоборцев, проживающих в Ростовской и Тульской

областях. Остававшиеся в Грузии в силу экономических причин

оказались с начала 90-х годов отрезанными от остальных

духоборцев и не могли приезжать на заседания совета. Потом

там появился свой лидер, и кавказские духоборцы, занятые

проблемой выживания, совершенно отстранились от

сотрудничества с советом Объединения. Весной 1997 г. внутри

общины духоборцев села Гореловка в Грузии произошел раскол

на экономической почве, который осложнился конфликтом части

духоборцев с армянскими властями Ниноцминдского района (это

район с почти моноэтничным армянским населением). Эта часть

духоборцев в настоящее время вынуждена искать пути для

миграции в Россию, но все переговоры с государственными

ведомствами они ведут помимо Объединения духоборцев России.

Иными словами, и у молокан, и у духоборцев с середины 90-х

годов начался процесс децентрализации руководящих органов.

Эти органы оказались невостребованными, их инициативы часто

не только не находили поддержки на местах, но воспринимались

как желание руководителей узурпировать власть. |

The ADR Council gradually

became an organization that represented the interests of

Dukhobors living in Rostov and Tula oblasts, since from the

early 1990s on the Dukhobors remaining in the Republic of

Georgia had been economically segregated from the rest of

the Dukhobors and could not attend council meetings. The

Dukhobors of the Caucasus subsequently acquired a leader of

their own and, preoccupied with the problem of simply

surviving, completely withdrew from cooperation with the ADR

Council. In the spring of 1997 the Dukhobor community in the

village of Gorelovka, Republic of Georgia, underwent an

economic schism, which was compounded by a conflict between

certain Dukhobors and the Armenian authorities of

Ninotsmindskii raion (whose population is almost exclusively

Armenian). These Dukhobors are being forced to look for ways

of migrating to Russia, but they are bypassing the ADR in

their negotiations with various state agencies. By the

mid-1990s, that is, managerial decentralization had begun

for both the [Spiritual

Christians] Molokans and Dukhobors.

Managerial bodies became irrelevant, and often their

initiatives not only failed to win local support but were

even perceived as a desire on the part of the leadership to

usurp power. |

| Несмотря на призывы возродить

духоборчество и молоканство, раздававшиеся в начале 90-х, на

деле мало что изменилось. Религиозные общины духоборцев

по-прежнему малочисленны и не регистрируются, так как просто

не видят в этом смысла. Среди молокан тоже не наблюдается

особого стремления узаконить свою деятельность, хотя

некоторые недавно возникшие общины, особенно

переселенческие, юридически оформились. Продолжают

регистрироваться в основном те общины, которые узаконили

свою деятельность еще в годы советской власти. Для некоторых

из них мотивировка остается прежней: сохранить за собой или

получить молитвенный дом или хотя бы квартиру. При анкетном

опросе выяснилось, что многие зарегистрированные молоканские

общины не имеют постоянного места для молений, так как

местные власти тянут с выделением помещения. Половина

опрошенных вообще не считает, что регистрация дает им

какое-либо преимущество. Среди тех, кто ответил на этот

вопрос утвердительно, большинство считает, что главным

преимуществом регистрации является получение общиной

юридического статуса, дающего возможность вступать в диалог

с представителями местной власти … опять же с целью

получения помещения. |

Despite calls in the early

1990s for the revival of [Spiritual

Christianity] Dukhoborism and Molokanism,

little has actually changed. Dukhobor religious communities

are still small in number and remain unregistered, because

they simply see no point to registration. Molokans are also

not eager to legitimize their activities, although some new

communities, especially those consisting of recent settlers,

have gone through the legal formalities. Most of the

communities that legitimized their activities in Soviet

times also continue to register. For some of them, the

motivation remains what it has always been: to retain or

acquire a prayer house or at least an apartment in which to

hold prayer meetings, a survey having revealed that many

registered Molokan communities have no permanent place for

prayer due to the local authorities’ dilatoriness in the

allocation of premises. Half of those surveyed did not

believe that registration would bring them any advantages

whatsoever, and those who thought that it would wanted it

mainly to give the community legal status, which would allow

it to engage in dialogue with the local authorities, again

with a view to acquiring premises.

|

| Незарегистрированные общины

по-прежнему собираются в частных домах и квартирах. Они

нашли возможность иметь и свой счет. Один из членов общины,

обычно казначей, заводит сберегательную книжку, на которой

лежат общественные деньги, и оформляет завещание на имя

другого члена общины. Этот вариант «расчетного счета»

достаточно распространен и в других конфессиях. |

The unregistered communities

continue to gather in private homes and apartments, and they

have even found a way to open their own bank accounts [which normally requires registration].

One community member, usually the treasurer, maintains a

savings account into which the group’s money is deposited,

making another community member the account beneficiary.

This variant of the “commercial account” is quite widespread

among other denominations, too. |

| Несмотря на то, что у молокан

и духоборцев еще свежи воспоминания о репрессиях, сейчас

редко кто отказ от регистрации мотивирует опасением их

возобновления. Прежде всего это можно объяснить, как и

прежде, отсутствием какой-либо деятельности, кроме

традиционных молитвенных собраний. |

Although [Spiritual Christian] Molokan

and Dukhobor memories of repression are still

fresh, it is unlikely that anyone would explain the refusal

to register by concern over a possible reprise. The primary

explanation proffered by the Molokans is the time-honored

one: that they do not do anything except hold their

traditional prayer meetings. |

| Никаких радикальных изменений

в возрастном составе молоканских и духоборческих духовных

общин за 90-е годы не произошло. Опыта какой-то специальной

работы с детьми и молодежью ни у молокан, ни у духоборцев не

было. Раньше дети росли в религиозной среде, и с детства

родители обучали их псалмам, молокане приобщали и к чтению

Библии. Все было органично и естественно. В советское время

атеистическое воспитание в школе у большинства совершенно

отбивало желание приобщиться к вере отцов, хотя после ухода

на пенсию некоторая, безусловно, меньшая часть людей

возвращалась к своим истокам. Несомненно, большую роль

сыграл официальный запрет на миссионерскую деятельность

религиозных организаций. Даже в селах, целиком состоящих из

молокан и духоборцев, где раньше было много детей и

молодежи, старшее поколение не пыталось привлечь их к

религиозной жизни общин. На вопрос о причинах сложившейся

ситуации старики обычно отвечали, что к Богу насильно не

приведешь. |

During the 1990s there was no

radical change in the age composition of the [Spiritual Christian] Molokan

and Dukhobor religious communities, neither of

which has had any specific experience in working with

children and young people. Previously, children grew up in a

religious environment, being taught the psalms by their

parents, while the Molokans also introduced their children

to Bible reading. It all came about organically and

naturally. In Soviet times atheist indoctrination in schools

robbed most children of any desire to share the faith of

their fathers, although some — unquestionably a minority —

returned to their roots in retirement. Undoubtedly, the

official ban on proselytization also played a large role.

Even in villages inhabited only by [Spiritual

Christians] Molokans and Dukhobors,

where there had once been many children and young people,

the older generation has made no attempt to draw them into

the communities’ religious life. When asked why, the elderly

normally reply that no one can be brought to God by force.

[The dominant factor is economics. Good paying jobs can

only be found in large cities, where there are no

Spiritual Christian meeting halls. In 2007, I met many

families who have a member, child or husband, that moved

to Moscow, St. Petersburg, or Rostov-na-donu for work,

where even the lowest paying jobs pay 2 or 3 times more

than outside the largest cities. Senior Presbyter

Shchetinkin admitted that the largest Molokan

congregations in Russia would now be in the big cities if

meeting buildings existed there. In March 2007, I met a

Russian-born pastor from Rostov, living in Phoenix,

Arizona, who reported that about 1000 Molokans were

attending his evangelic church in Rostov because they had

no other place to attend.]

|

Демократизация общественной

жизни и снятие запретов на деятельность религиозных

организаций, казалось бы, должны были изменить отношение к

миссионерской деятельности, особенно с целью привлечения

молодежи. Молокане раньше, чем духоборцы, забили тревогу по

поводу отсутствия у них молодого пополнения. Привлекать

молодежь в собрания, открывать воскресные школы для детей с

первых номеров призывал журнал «Духовный христианин». В

информационном листке «Весть» Цахкадзорская община молокан

(Армения) сообщала об открытии детской воскресной школы и

призывала остальных последовать этому примеру(6). С первого же года работы совет

Союза общин ДХМ поставил на повестку дня вопрос о молодежи.

Старший пресвитер Союза Т. Щетинкин обратился к женщинам со

страниц «Духовного христианина», призывая воспитывать детей

в молоканской вере: «… весь живой человеческий мир

воспитывается у вас на руках, и те слова, которые слышат

дети, они их впитывают с грудным молоком»(7).

|

One might have thought that

the democratization of public life and the lifting of

prohibitions on religious organizations would have changed

attitudes toward proselytization, especially to attract

young people. As it happened, the Molokans preceded the

Dukhobors in sounding the alarm on the younger generation’s

absence. From its earliest issues, the periodical Dukhovnyi khristianin [Spiritual Christian]

recommended encouraging young people to attend meetings and

opening Sunday schools for children. In the Vest’ fact sheet, the

Molokan community in Tsakhkadzor (Armenia) reported that it

had launched a Sunday school and called on other communities