Dukh-i-zhizniki in America

An update of Molokans in America (Berokoff, 1969). — IN-PROGRESS

Enhanced and edited

by Andrei Conovaloff, since 2013. Send comments to

Administrator @ Molokane. org

Contents

- Demens Chose Los Angeles

Chapter 2 — The First Years <Chapter 1 — Contents — Chapter 3>

Demens Chose Los Angeles

PAGE 32 The city

chosen* by the Spiritual Christians Molokans for their haven was in many

respects ideal for their purpose though they may not have been

aware of the fact at the time. Los Angeles in those days was not

the overcrowded, smog ridden city it is today in 1969. Indeed, by present day

standards it could not be called a city but a pleasant, quiet,

overgrown town with a population of 102,000 according to the

census of 1900. It was a center of a fertile agricultural

district populated mostly by elderly people seeking health or a

comfortable place of retirement in a healthy, mild climate.

* Demens chose the city for them. These Spiritual Christians were escorted, personally diverted from Canada, to Los Angeles by Russian-American tycoon Piotr Alexeyevitch Dementiev. His American name Peter Demens is often mis-spelled in the press. He provided jobs in his lumber yard and commercial laundry in Los Angeles; and, with his Russian friends, he helped them negotiate farm colonies in Hawaii and Mexico, and explore many sites in North America.

Few, if any, immigrants came here directly from their port of

entry. Although there were some foreign speaking

immigrants here when the first Spiritual

Christians Molokans arrived, mostly Jews ,

Japanese, Chinese, Slavs, Mexicans, and

Italians. These came after spending some time in the cities of

the Eastern seaboard, and having heard of the wonderful climate

in Southern California, its roomy new towns and cities, fled the

crowded tenements of the East and remained here permanently.

Southern California businesses launched a

huge advertising campaign to lure "white" investors and

"white" workers to their "White Spot."

But the Spiritual Christians Molokans, profiting from the two year experience of the Agaltsoff group, were spared these needless trials when they came directly to Los Angeles where they met Demens. Had they by some unfortunate mischance landed in New York, Boston or Philadelphia as hundreds of thousands of other immigrants did and were per force compelled to live in the crowded, unheated, rat-infested slums of those cities, they would have abandoned their place of refuge and fled headlong back to their village homes as fast as they were able to save enough money to do so because such living conditions were simply not for them.

In the first place they could not have endured life in a tenement house where dozens of families of all nationalities PAGE 33 lived together. Secondly, it was a positive necessity for them to have a place of worship isolated from crowds of non-Spiritual Christians Molokans. It would have been utterly impossible for them to conduct their worship, their holiday feasts, their wedding or funeral ceremonies in the prescribed manner. It would also have been impossible for them to conduct prayer services in their own homes as they were accustomed to do because other dwellers of the multi-familied tenements would have forced them to give up the custom. Not so. The Spiritual Christians lived in cramped conditions with outsiders as neighbors in the slums of Los Angeles. Many slept in horse barns and dirt floor shacks built from scrap materials. This was the first climate these people ever lived in with no winter snow. Many tenements and cooperative housing in large eastern cities had community rooms which would have provided space for assembly until they bought their own property, as did similar immigrant groups in those cities. All large American cities had settlement houses and immigrant aid societies, like those found in Los Angeles.

On the other hand, Los Angeles, being a new city with no natural obstacles to expansion, was able to spread itself, allowing space between houses as well as front and back yards for the use of each occupant. Its houses too, were relatively newer with individual plumbing and in some cases, wired for electricity, which was not the case in the East. All these things combined, permitted the Spiritual Christians Molokans the environment to practice their religions undisturbed. Not so. Several police reports were filed, and large hearings held about the noisy Russian Holy Jumpers disturbing the peace. Much effort was expended to move them out of Los Angeles to any rural area, including Mexico and South America. At least a dozen land agents approached them.

After three years or so in Los Angeles, the more enterprising ones were able to purchase their own homes. These immediately proceeded to install in their back yards the typically Russian institution, the "bania" (Russian: bath house), which, for a fee of ten cents were utilized by those who did not possess such a luxury. It was not very long before other families also bad the added luxury of a home-made brick bake oven in their back yards where delicious bread was made by the enterprising housewives. Many in cramped houses cooked outdoors on fire, which injured people and burned houses.

Although during the first years the Spiritual

Christians Molokan families made the utmost use of

each house by crowding each bedroom, there was, nevertheless,

some houses where a large room was made available for the

community as an assembly hall (sobraniya)

a church and since the houses on either side

were usually occupied by Spiritual

Christians Molokan families, there was no

disruptive interference from neighbors or from hoodlums.

The section of the city where the Spiritual Christians Molokans first settled was in a close

proximity to all their needs. Lumber yards, cold PAGE 34 storage plants

and the rail road yards where work was to be found were all

within walking distance. The downtown shopping district was not

more than half mile away.

The

first to arrive were 6 families of led by Vassili

Gavrilovitch Pivovaroff In mid-1904, Spiritual Christians arriving in Los Angeles

first settled northwest of the train station around the

Bethlehem Institutions where they got extensive free help in

the Russian language, free services and free use of

facilities. During the first decade, many lived in small

crowded wood shacks, some with dirt floors and outhouses, on

the cheapest land.

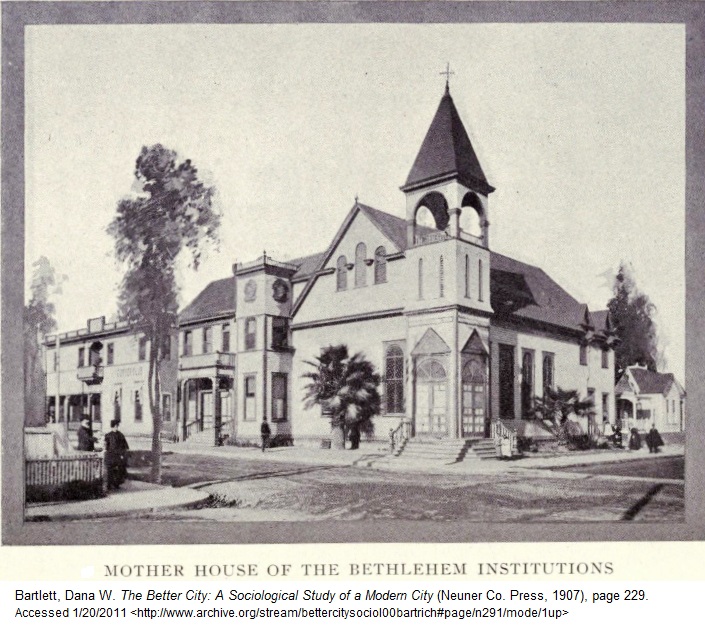

Bethlehem district

The

Bethlehem Institutes are the Church (marked), Men's Hotel

(north side of Church), Bathhouse (south across street),

several Coffee Houses and Bartlett supervised the

Stimson-Lafayette Industrial School where Spiritual

Christians held meetings (sobranie).

The Bethlehem Institution tried to provide every service

needed by the poor and to assimilate foreigners — food, baths, housing, medical, education,

legal, language, citizenship, furniture, job training and

placement, meeting place, etc.

For 6 weeks in February and March 1905, 2000 American Christians marched, played music and sang daily through the east-side slums in huge evangelic parades to save sinners (mainly prostitutes and drunks). The Bethlehem Institute hosted the guest marchers. More than 400 arriving Spiritual Christians witnessed the events, which probably inspired Bezayeff to perform his own spiritual "maneuvers" (маневров : manevrov). Bezayeff trained marchers in the Stimson-Lafayette Industrial School lot before taking his spiritual troops to the streets. At least one of his spiritual marches went to City Hall, a 1.5 mile round trip.

The Russian Economical Association Company (R.E.A.C.) was formed in January 1907 to own and manage a co-operative store and bakery at 209 N. Vignes, at the southwest corner of Banning street. The manager was paid $11/week and every clerk was a limited stockholder. It was a communal business needed in the neighborhood, but failed in 1908 due to mismanagement and a suit by one man for back wages.

The Bethlehem district mapped above was bounded on the west by Alameda street, on the East by the river bed, on the South by East First Street and on the North by Aliso Street. The name "Bethlehem district" was created for this history because this historic slum neighborhood was never officially named. Reporters often referred to a "foreign district" of which this was a part. This Bethlehem district was part of the 8th Ward "Warehouse District" which today is called the Arts District, also called East of Alameda. In the early 1900s it was part of a large blighted over-crowed area with shacks, bars, prostitutes, factories and businesses. Many of the immigrants lived in garage horse barns with dirt floors and cooked outdoors.

Despite the fact that the gas works, a soap factory and a

brewery were located on the perimeter of the area, it was still

primarily a residential district, populated mostly by immigrant Jews, Mexicans, Japanese and

others with a good school in the very center of the area. The

Amelia Street School where many pioneer families attended

classes became for many Spiritual

Christian Molokan

children, from 8 to 14 years old, their first

contact with American culture.

Dr. Rev. Dana

W. Bartlett,

superintendent, Bethlehem Institutions

Within the area there was also a church and a settlement

house managed by a sincere devout

Christian, the Rev.

Dr. Dana W. Bartlett who was the first American-born to befriend the Spiritual Christians Molokans in Los

Angeles and who later became a close friend of their leading

elders and who was also very helpful to them in many ways and

was respected by all who came in contact with him.

This is what Dr. Bartlett said of his very first contact with

the Spiritual Christians Molokan people:

The

flight into refuge. — The appearance of the Spiritual

Christians Molokans

in Los Angeles was as sudden as it was unobtrusive. Rev Dana

Bartlett, an eye witness, tells the story thus:

"One bright

morning in the winter of 1905 [1904?] as I was walking along

the street near the Bethlehem Institute, an institutional

church, I perceived many new and strange people, Russian

peasants as they later turned out to be. They seemed quiet,

industrious, dignified, preoccupied with their own affairs. I

talked sign language to them, inviting them to come to my

church Photo right]. In a short time these people became the

object of much attention in the neighborhood. Large numbers of

[Spiritual Christians] Molokans continued to settle on and

around Vignes and First Streets converting the district into a

veritable Russian village." [Footnote: Quoted from "The

Pilgrims of Russian Town" by Pauline V. Young. Page 11]

Young, Pauline V. The Pilgrims Of Russian-town:

Обшество Духовеныхъ Христиiанъ Прыгуновъ въ Америкѣ: The

Community of Spiritual Christian Jumpers in America : The

Struggles of a Primitive Religious Society To Maintain

Itself in an Urban Environment. Chicago, 1932,

pages 155-156.

NOTE: In his books Bartlett called them "Russians" or the "Brotherhood of Spiritual Christians," not Molokans as stated by Young, whose book was edited by Berokoff. Also see a Christian cross on the Bethlehem church steeple which was cropped in Mohoff, George W. and Jack P. Valoff, A Stroll Through Russian Town, 1996, page 234.

Chapter VII: The Outer World:

Citizenship And Americanization Programs

...

Informal

approach to Americanization. — In contrast with the

proselytizers, there are other individuals who established

lasting contacts with the [Spiritual Christians] Molokans.

Among these, Dr. Dana Bartlett,(1) former pastor, is perhaps

the most outstanding American leader in the [Spiritual

Christian] Molokan

Colony. He is one of the most venerated persons—a "living

angel"—which the group found in America. Without exception,

every [Spiritual Christian] Molokan who has come in contact with

him pays him high respect and refers to his lack of ulterior

motives in helping them: "Dr. Bartlett will never be forgotten

by the [Spiritual Christians] Molokans. He befriended us as soon as

we had arrived here. He stood ready to help us without trying

to impose his beliefs. He asked us what we needed and never

tried to decide for us what he thought we needed."

Dr. Bartlett's own statement is significant:

The [Spiritual

Christians] Molokans

were convinced that I was not trying to win them over to my

church. Their religion has considerable merit, and I worked on the assumption that

a good [Spiritual

Christian] Molokan is better than a poor Methodist.(2)

They were cordial and trusted me, confided in me all sorts of

problems. The first few years were very trying for them.

Strange, idealistic, tongue-tied, they were exploited by many

real estate men who sold them dry, sandy desert land with no

prospects for water or crops. They moved their families

hundreds of miles away from the main Colony, only to come back

penniless, and a few of them broken in health. If they came to

me before the contracts were signed, I could generally ward

off an unscrupulous deal. ....

These people have genius in community organization of the type

which they are accustomed to, but they are at a loss in the

city. They have had enough misfortune to distrust social

workers and social reformers alike and soon came to consider

them intruders.(3)

- Others are Fannie Bixby Spencer, who carried on a form of settlement work for children of working mothers, and Michael Leshing, Russian by birth, who was friend and adviser to many families.

- Italics added.

- Document 51b. Personal interview.

— End The

Pilgrims Of Russian-town quote.

Bartlett "The most useful citizen of Los Angeles" (1860 - 1941) specialized in urban renewal and immigrant assimilation. He was a graduate of Chicago theological Seminary, then an ordained Congregational church minister who worked in Utah, Missouri, and California where he was assigned to manage the church charity mission in the slums. He is widely known for advocacy for the poor, homeless, alcoholics, immigrants, 3 books, lectures, lobbying, city planning, running for city council (8th Ward), and developing the 6-lot campus of social services — the Bethlehem Institutes. He served as Pastor and Supervisor at Bethlehem for 17 years (1896-1913) until it was closed by the Municipal Charities Commission for poor management. Bartlett retired as pastoral consultant of First Congregational Church, Los Angeles. Spiritual Christians sang at his funeral in 1941.

The Brotherhood of Spiritual Christians

arrived at the right time and place to be assimilated. The

Bethlehem Institutions was a full-service agency that provided

nearly everything the poor uneducated immigrants needed to

become tax-paying American citizens — free food, baths,

laundry, temporary housing, English lessons, citizenship

classes, job training and placement, adult education in

Russian, medical care, meeting rooms, cooperative store,

recreation, legal help, etc. Those who participated quickly

assimilated, while the most introverted avoided outside help.

After Bethlehem closed in 1913 immigrant guidance continued

when the Y.W.C.A. started the International Institute in 1914

and the schools hired 47 Home Teachers by 1923.

PAGE 35 The Spiritual Christians Molokans lost no

time in establishing themselves in the district. In 1906 they

already had their own cooperative

grocery store and meat market on the corner of Vignes and Turner

Streets where real Russian Molokan bread,

home baked in their own brick ovens, as well as meat butchered

by themselves in local Jewish slaughter houses could be bought.

Matvey Konovaloff also had a grocery store

at 310 Amelia street.

At first the

Spiritual Christians were invited to conduct their own

Saturday and Sunday meetings (sobranie) in the

Bethlehem Church, because there were very few suitable rooms

in their overcrowded houses. Their traditional Russian

service required a large room with a table and movable

stacking backless benches. The American church, arranged

with heavy backed benches and a pulpit, was awkward for

theses Russians, especially the most zealous when they

arrived for whom the cross on the steeple may have been

another factor.

In 1906 too, through the efforts of Dr. Bartlett, a regular assembly church building

main hall of the Stimson-Lafayette

Industrial School, managed by Barlett, located in the

center of the district, on Lafayette Street between Jackson and

Turner Streets was made available to them. It was quite roomy,

with a large vacant lot in the back where, as occasion demanded

many samovars were gathered and prepared for the use of the

"sobraniia" [Russian:

meeting].

They occupied this building until 1910. After that time the

great majority moved east of the river bed to the district now

know as "Flats", or the "Flat". The

assembly church* too was then moved to South Clarence

Street at 1st street address to

the building now known as Klubnikin's Podval or Shubin's sobranie.

* Note that Berokoff refers to his congregation as "the church", as if it was the main congregation in Bethlehem and in the Flat(s). Throughout the book, his context is biased towards the perspective of his prophet, his presbyter, his faith, and his congregation — which he erroneously calls "Molokan." Berokoff avoids the history of other congregations which compose the majority of the ethno-religious enclave from Russia around him.

Immigrants from Russia settled in in the

Flat(s) mainly for socio-economic reasons — jobs and cheap

housing and food.

- The first to arrive in May 1904 led by V.G. Pivovaroff took the cheapest shanty housing available, but had no meeting hall.

- Demens' commercial laundry and lumber yard were on the south side of The Flat(s).

- After 1907, slum conditions on the east side of downtown Los Angeles (Chinatown, Sonora-town, The Flats(s)) were somewhat cleaned up by the city housing authority and regularly inspected.

- In 1910, the Y.W.C.A. opened a local

branch of International Institute on Boyle Avenue, north of

First Street (original location).

- In 1914, The Bethlehem Institutes were closed by a city auditing commission due to poor management.

- After WWI more than 1000 Spiritual

Christian immigrants from Russia, who fled the city to rural

colonies during the "bride-selling"

scandal, returned. If an entire congregation returned it

remained independent, while returning segments of a

congregation rejoined those who stayed in L.A.

Initially, each major congregation in the

Flat(s) had its own store, transplanted from Russia and

supported mainly by their own congregation. The same system of

multiple stores occurred in San Francisco for the various

Molokan congregations on Potrero Hill. Shopping at the store

of another congregation was religiously incorrect,

particularly for the most zealous. Congregations with no store

had a choice of where to shop.

When Dr. Bartlett said that the Brotherhood of Spiritual

Christians Molokans*

soon became an object of much attention he knew whereof he was

speaking, for it must be said that their very appearance invited

attention from various quarters. The men especially, wearing

their beards long and clinging to their peasant clothes and

boots, their shirts worn outside their trousers and girded like

smocks, some even wearing home-made peasant pants, they were

radically different from any other newly arrived immigrant seen

in America.

* In his 1908 book The Better City, Bartlett twice called them the "Brotherhood of Spiritual Christians" (pages 80 and 229), and "Russian" (7 times). No other terms were used.

The women too, with their black woolen shawls and their

vari-colored, bright-hued Sunday clothes, were different from

any women on the streets of Los Angeles. Within

a few decades the bright Russian peasant colors and patterns,

still seen on Staroobriadsty (Old Ritualists) near

Woodburn, Oregon, were normalized to pastels and shades of

white, while the women added lace, typical of wealthy

Russians. Soon many fashionably dressed more like Lev and

Sophia Tolstoy than the style of Russian peasant who

immigrated.

Of necessity, they were compelled to walk daily along East First street, the main thoroughfare adjacent to their residential area. This thoroughfare abounded in saloons and pool rooms with the usual complement of the type of people that frequented such places. These hooligans naturally thought it was a great sport to tease and abuse these strange people, at times going PAGE 36 far beyond the limits of innocent fun. A common prank was yanking a man's beard and running away. The Spiritual Christians Molokans endured this as long as they could after which the hot-blooded younger men took forceful measures of retaliation. This had the desired effect and they were thereafter left alone. Fortunately, however, not many people in Los Angeles were of that ilk. The great majority of Americans of that time were kindly, hospitable, church-going, religious people. The principal and the teachers of the neighborhood school in particular, were understanding and sympathetic when their primary grades were filled to capacity with children in peasant clothes and knowing not a word of English. Their problems were aggravated by the fact that their classes were composed of children whose ages varied from 7 to 13 and 14 years.

Of course the older children, those 12 and 13 years of age soon

reached the permissible age of 14 to quit school and went to

work to help the family bread winner. The remainder were

advanced rapidly until they caught up with other children of

their age. It must be remembered that the peak year of Spiritual Christians Molokan

immigration —1907 — was a year of severe unemployment. Work,

especially for men, was impossible to find. It was a little

easier for the women to find work, usually in laundries at $5.00

and $6.00 per 60 hour week. [Sokoloff,

page 5] Others found

work doing housework in private homes at 25 cents an hour.

Helped out by older school boys who sold newspapers on the down

town streets, the women were the sole means of support for many

families until the employment for men picked up in the lumber

yards as the building boom slowly regained momentum.

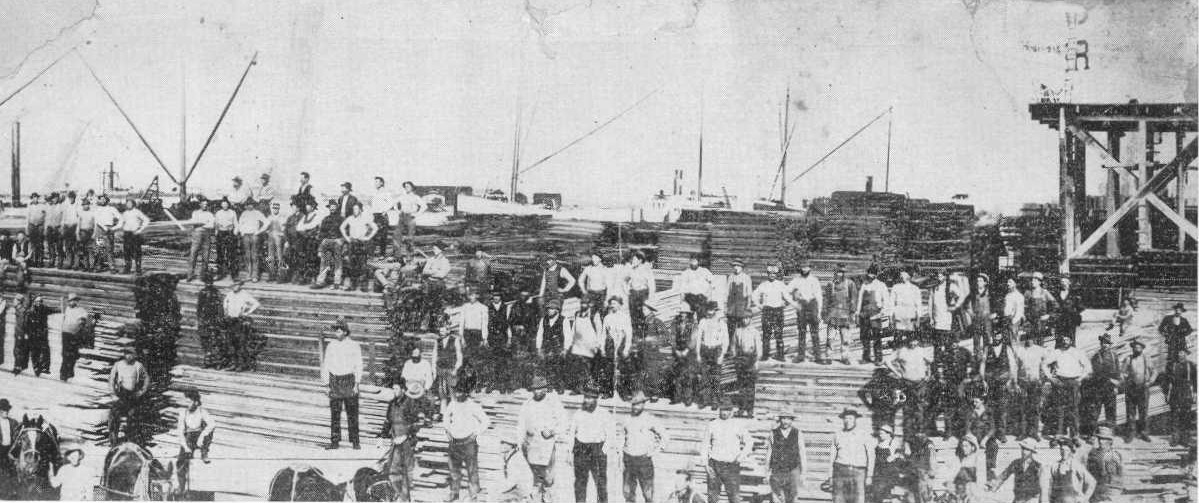

Lumber yard in

Wilmington Port

of Los Angeles showing many Spiritual Christian Molokan

men among other unloading lumber-carrying ships in 1914. Photo Courtesy of James A.

Samarin. Click

to Enlarge

Mystery Woman, Land Donor Insulted

There was yet another person attracted to the Spiritual Christians Molokans and whose appearance among them has since become a fascinating mystery almost reaching the proportions of a legend discussed among the older Dukh-i-zhizniki Molokans to this day, being even honored by a paragraph in one of their more popular songs (song 446, fifth stanza, second verse.)

| |

Song 466 |

|

Песнь 446 |

| This is the place we all know is a peaceful region, | Это место всем известно, оно есть мирный край; | ||

| the

Holy Spirit expected us here many years ago. |

здесь Святой Дух нас

ожидал, много лет тому назад. |

PAGE 37 On a summer Sunday morning in 1904, when there were yet only a few Prygun Molokan families in Los Angeles, they were gathered together in the house of one of the elders for worship led by V. G. Pivovaroff, when there came to them an elderly American woman of commanding appearance and accompanied by another woman maybe Madame Verra de Blumenthal who spoke Russian and through whom the elderly woman proceeded to inform them that she was there to ascertain for herself whether or not they were the people she saw in a vision forty years previously [~1864], and who were to be welcomed by her to America with a gift of land in the vicinity of Los Angeles. One oral legend says it was near Signal Hill, north Long Beach, where oil was found in 1921.

She told them further that she journeyed to Canada to see the Doukhobors when they first came there but that they were not the people she was expecting. However, she was now convinced that the Spiritual Christians Molokans were indeed the people of her vision but she wondered why did it take them so long to get here. Furthermore, the people of her vision were exactly like them in appearance and she pleaded with them not to change their religion nor their appearance in any manner else the grace of God and His mercy will no longer be with them.

The Maksimisty Molokans, wrongly suspecting ulterior motives behind such fantastic story, did not respond with tact or gratitude nor asked for time to consider the matter but were rather careless in their remarks among themselves, one member saying in Russian: "Who is this pork-eater that we should pay attention to her?" When this remark was translated to her, she, being a vegetarian, was extremely hurt and terminated the conversation and left without leaving her name or address or the location of the land she proposed to donate.

Although the whole story sounds unreal, the fact remains that there, are people alive today who witnessed the whole proceedings but who were too young at the time to be duly concerned; therefore they could not provide the necessary details that the story deserves. Nevertheless, the story could not be PAGE 38 dismissed, as fiction but will probably remain a fascinating mystery and a subject of conversation for a long time to come.

In Chapter 9: Conclusion, page 154, Berokoff laments:

* Berokoff states the "refuge" of Klubnikin's prophesy, and his faith, is within the state of California.

I speculate that the woman may have been a matron of one of the tycoon families who developed Southern California (Bixby, Clark, Hellman, Huntington), some of whom gave land to settlers; or from one of the emerging communal settlements; and the translator could have been Madame Verra de Blumenthal, Madame Demens, or any of a dozen Russian-speakers associated with the Bethlehem mission. If anyone can add to this or add to any other story, please do.

Imagine what if the Spiritual Christians got this free land. The most zealous peasants would have immediately argued, the faith groups split, and a majority preferring the city, many in anticipation of rushing back to Mt. Ararat. In the city they did not manage their own co-op REAC store, meet or live together, and for generations sabotaged their common U.M.C.A.

In addition to their struggle to exist in a strange land, the Pryguny Molokans very early in their life in America were faced with a problem that has plagued them for many years, even to this day, one which God alone could resolve. The same type of problem had to be faced by all nationalities that emigrated to America but notably by the Jews who also had to struggle with it unsuccessfully for many years who, in the end had to learn to live with it. This problem was intermarriage or assimilation with the local population.

It was 1909 that an event occurred that was so portentous in its implications, for it brought the Pryguny Molokans for the first time face to face with the problem of intermarriage. A young Prygun Molokan girl of about 17 fell in love with an American youth and, without informing her parents eloped with him and married him.

Learning of this, the parents of the girl, helpless in their grief and ignorant of the ways of the new country enlisted the aid of the leading elders and retained a Russian speaking attorney [Mark Lev?] to have the marriage annulled. But of course the sympathies of the public, the police and the courts were with the young couple, especially after the girl informed the court that she fled her home to evade being sold in marriage to a Prygun Molokan boy she did not love.

The parents, in answer to that charge, explained that it was a custom among their people to arrange marriage for their children as in the old country, and as there were more Prygun Molokan boys of marriageable age in the Prygun Molokan community than girls, there was much competition for available girls, and since their daughter was in such a demand, the parents of one suitor offered to reimburse the amount of the girl's passage to America if their son was accepted as a suitor, further explaining that PAGE 39 the negotiations were still in the preliminary stage and that there was no intention to force the girl into marriage against her will.

Although the elders and friends supported the testimony of the parents, the court was not convinced and the marriage was allowed to stand.

The newspapers, as usual, made a sensation of the case, playing it up in headlines for 3 years about a week before dropping it for other sensations.

The postscript to the story is typical of the many others of similar nature. The parents held back their forgiveness for a long time but eventually relented, but in any case the marriage eventually broke up and the woman returned to the Prygun Molokan community and died soon after and was buried without being accorded the full Prygun Molokan rites.

Berokoff avoided reporting detail : the extent of incidents, dates, addresses, congregations, names and ages. We know Berokoff and others proofread and edited Young's Pilgrims of Russiantown, which also avoided these facts. Compare Berokoff above to Young, page 108:

"The selection of a partner by the parents is rooted in familial organization. All members of the older generation were "given away" by their parents, and frequently without much previous intimation as to the prospective mates, who accepted the parents' choice without much reflection. The Dukh-i-zhiznikiBerokoff refers to "an event" in 1909 which was in the news for "about a week." Young reported "two cases of suicide" and arranged marriages are "almost an impossibility" due to poverty. In contrast, many news reports up to the 1920s suggest that both Berokoff and Young denied, negated and/or revised history. The "event" as reported by Berokoff cannot yet be correlated with a single incident reported in the news, which suggests he is reporting an event not covered in the news, or he scrambled his oral history again.Molokanstell of only two cases of suicide because of dissatisfaction with parents' decision regarding the prospective mate. In America, however, the children are allowed to choose for themselves ....

"There are hardly any marriages for money ... social and economic organizations make such marriages almost an impossibility."

Newspapers reported many cases of child abuse and forced, arranged and unregistered (illegal) marriages from 1909 through 1915 in Los Angeles county, and from 1911 through 1920 in Arizona. For a century, into the 2000s, diaspora oral history reports zealous control of dating, marriage and divorce, with hundreds, probably over a thousand, banned and bullied from their heritage Dukh-i-zhiznik faiths. The total number of cases, types, the defendants identities and outcomes is vast. Here I summarize cases from a few public records. Names are spelled as published.

- 1909

- In April 1909, a failed

murder-suicide shocked the community on Kushcha (Feast of Tabernacles)

Sunday. Because sweethearts

were forbidden by her father to marry, Alexis Kottoff

23 shot Anna Sossoeff 16, and shot himself. Both nearly

died in hospital. He was imprisoned 5 years. Zealous

father Alex Sossoeff was in debt and needed his daughter

to work for him, and not marry an educated liberal

"freethinking" (Molokan?) boy from a different

faith.

- In August

1909, widowed Willie John Kobzeff 22 (parents: John

& Mary), married Lillian

Clarke 34 (parents English & Scottish), at the Boyle

Heights Methodist Episcopal Church. In October 1909 news

reported his relatives broken up the marriage, told Lillian he

had a wife in Russia, and shipped Willie back

to Russia.

- 1911-1915 — A series of

"bride-selling" court cases made national news, led by Elsie

John Novikoff who protested her arranged marriage for $500

and beating by her father. Fortunately she worked as a maid

and her wealthy employer hired an attorney. A "mass meeting"

was held at Podval sobraniya (Berokoff's meeting

hall) on 24 December 1911 to petition the Governor of

California to investigate and apologize to the immigrants.

100s attended the court hearings which exposed how their

sacred traditions from Russia were not legal in this land of

refuge. Several bride-selling cases were reported for nearly

3 years. Fortunately the hearings were under the

jurisdiction of Judge Wilbur, a board member of the

Bethlehem Institutions who worked closely with Dr. Rev.

Bartlett, and knew many of these families from previous

cases. The judge imposed no punishment, but ordered the

Spiritual Christians to obey US. laws by promising they

would no longer exchange money for brides or arrange

marriages, register marriages, and not punish their kids.

Wilbur graciously offered to re-do all unregistered

marriages legally in his court for no charge. The first to

be married by this noviye obryad (new ritual) was a

son of leader F.M. Shubin who set the example for others in

the city to follow. Those who had fled the city were able to

maintain an isolated culture for a few more years, like

Arizona below.

- 1912 — Simultaneously (and

very similar to non-Doukhobor Spiritual Christians in Los

Angeles), in British Columbia, Canada, the Christian

Communities of Universal Brotherhood (C.C.U.B.),

communal

Doukhobors (obshchei dukhobortsy),

were accused in court of 4 allegations, which were legally

examined in public hearings for 4 months, in 3 towns in

BC and 4 towns in SK, gathering testimony from 110

witnesses aided by several

lawyers and scholars. The 3rd allegation was

substantiated but not prosecuted: "(3.) It was objected

that the peculiar [home] marriage ceremony, the fact

that the Community recognizes no outside authority, and

that it refuses to register births, deaths, and

marriages, ... " Obshchei dukhobortsy

also objected to the Public Schools Act. For violations,

the commissioner recommended fines to be more

effective than jail. (William Blakemore, Report

of Royal Commission on Matters Relating to the Sect of

Doukhobors in the Province of British Columbia, 1912,

page 64.)

- 1920 — 2 Arizona presbyters

were together fined $600 ($7,000

to $117,000 in 2015) for not registering marriages

since 1911. Many who believed they were being persecuted for

their religion in Los Angeles fled to other states. Maksimist

Mike P. Pivovaroff, who founded the first of four

colonies in Arizona in 1911, was jailed. Prygun presbyter

Homer (Foma) S. Bogdanoff avoided arrest but also appeared

in court. Their lawyer entered pleas of guilty. They were

fined $300 each (for each it was about year's wages each, or

the cost of a house or car) and ordered to re-do all

marriages. Their lawyer also testified that they recently

learned burial certificates were required, but no charges

were filed for those crimes.

| Definitions — What

are we talking about? During the Los Angeles court hearings, non-Spiritual Christian witnesses who spoke Russian (some were Jews) testified that what the journalists called "bride selling" has been a tradition in Euro-Asian countries for centuries where a child's destiny is assigned by parents. In the early 1900s the practice of buying a wife was strange and/or unfamiliar for Americans in government positions who were White Anglo-Saxon Protestants (WASPs, Northern European immigrants), many who knew of their traditional dowry, and maybe wreath money. The "bride selling" custom from Russia (Eastern Europe) seemed illegal to those whose ancestors gave gifts to newly weds after a wedding, but not to the family before a wedding. In contrast to Northern European customs, these Spiritual Christian immigrants from Russia were practicing an Old World custom variously translated today as bride price, bride ransom, wedding ransom, and bride buying (payment for the bride to the family). The common terms in Russian are kalym (калым), vykup nevesty (выкуп невесты) and svadebnyi vykup (свадебный выкуп). A common Russian term for a girl getting married is "to leave [the family home] for the husband" (выйти замуж : vyiti zamuzh), to probably live and work in her husband's extended family rural village. These terms do not appear in the Russian Synodal Bible used by the accused. In the Old Testament, the Hebrew Bible emphasized by Subbotniki, Pryguny, Maksimisty, Klubnikinisty, etc., a different term appears only twice in Exodus (Исход) 22:16–17— veno (вено). The term veno becomes clear in a modern Russian Bible, and in English.

A misunderstanding can easily occur if the reader only consults the King James Version which uses the Northern European term "endow her," which has a different meaning. Compare many English parallel renderings of Exodus 22:16 to see that more recent Bible translations chose the English term "bride price." In 2011, I documented kalym performed near Seattle, Washington, during a wedding of young Adventists from Russia, who are descendants of Molokane. About 200 immigrated in early the 2000s from from Krasnodar province, Northern Caucasus, Russia. For interested readers, a sample of kalym appears on a video of a Doukhobor wedding recorded in south Georgia S.S.R., in 1987, and can be seen on the Internet. Both of these groups from Russia may have modified their traditions during Soviet times. In the Doukhobor community in Georgia S.S.R., the groom had to pay ransom (vykup : выкуп) for his bride's stolen/missing shoe. In Washington state in 2011, the Adventist groom from Russia gave a gift credit card to enter the bride's house. In both cases the boys had a lot of fun negotiating with loud laughing persistent bridesmaids who blocked the entry door, acting as agents for their bride and demanding the highest price possible. See the first 11 minutes of The Doukhobors, Episode 7. (The entire documentary film is nearly 4 hours, with approximate English subtitles.) For many faiths rooted in Old Russia, kalym is part of their traditional wedding ceremony. Unfortunately, this custom, the "brides house" (devichnik : девичник), and other folk customs and foods have faded from use among the diaspora, often replaced with "American" forms, which are less embarrassing, less effort, and/or easier to buy than make. The most zealous Spiritual Christians that immigrated to Southern California apparently practiced a variation of kalym in which the parents negotiated and collected the bride price in advance, then told their kids who to marry. Some were promised, or betrothed, as young as babies by "notching the cradle," common among Spiritual Christians in Mexico and Iran (Persia). |

Though the court cases in Southern California (1911-1915) and Arizona (1920) may have stopped illegal "bride-selling," it did not deter zealous parents from imposing other controls on children who were rewarded with wealth (houses, land, rubbish trucks, money, inheritance, etc.) for marrying "right" or banished for marrying "wrong." Many young marrieds have been lavished with such gifts for obeying family, and many have been ostracized for not obeying. In 1984, Susan Leo Tolmachoff killed herself in Arizona with a hand-gun after her irate delusional father and his relatives forbade her to marry a divorced fellow in Kerman, California — Bill Pete ("Bosco") Nazaroff. Within a few years, her mother Jean M. Dobrinin-Tolmachoff, divorced her abusive husband.

In contrast to continual zealous parental control to marry into an acceptable, spiritually clean, Dukh-i-zhiznik family, the assimilated families often advise, some demand, that their children marry out of the Spiritual Christian faiths so they can invite their American friends to an American church wedding and reception, and will not have to perform a long traditional Spiritual Christian ceremony in Russian, kiss the same sex and old people, and be obligated to attend in-law (svakh : свах) family services for the rest of their life.

"Bride-price" appears in recent news online:

- An Ex-Husband Can No Longer Demand A Refund Of The 'Bride Price', by Amy Fallon, National Public Radio, NPR, August 21, 2015.

- Heated debate as MPs ban bride price refund, by Mercy Nalugo, Daily Monitor, March 4, 2013.

- Do

marriage contracts and payments affect divorce? (my

title), Dan Phung, paper for Anthropology 174 (Dr. White),

University of California at Irvine, 2002-2007.

Though many Spiritual Christians fled from Los Angeles to rural colonies, some back to Russia, claiming they were being persecuted by American laws allowing girls marry whom they want, mandatory marriage registration, foreign dress and education; those in San Francisco and northern California, had fewer legal problems — children immediately attended school, marriages were registered, many parents allowed interfaith marriages. However, problems with youth delinquency and elder resistance to naturalization was about the same in Los Angeles and San Francisco due to the clash of their foreign rural peasant culture with metropolitan life.

In Russia they were accustomed to independent life of a villager who tilled his land, planted his buckwheat, rye and wheat, raised enough potatoes, cabbages, carrots, sun flowers, cucumbers and other vegetables for his own use. There he could take time off for his annual holidays and when winter snow came, he rested for five or more months until the next spring whereas here, he, as well as his wife and the older children were in a set routine of nine and ten hours at work under the stern and watchful eye of the foreman six days a week, month after month and year after year, begging the foreman for time off for the annual holidays and, more often than not, losing his job for the devotion to his faith. But worst of all, there was no prospect of improvement in the routine.

PAGE 40 Some families, especially those who were comparatively well off in Russia, were soon disillusioned with America and returned to their village homes in Russia but, with exception of these few and despite the hardships, the great majority of those already in the U.S. heeded the advice of Klubnikin [Klubnikinisty], and being encouraged by elders who were steadfast (postoyannie)* in the belief of Klubnikin's prophesy, refused to consider the idea of return but began to look around for other means to escape the drudgery of city life, particularly to found a farming community somewhere, a desire that henceforth was never out of their minds.

* "Steadfast" is translated here into Russian to show the reader how the word is used positively by Dukh-i-zhizniki in context when describing their faith movement, but negatively about Molokane. When describing Molokane, postoyannie is an insult; but when describing Klubnikinisty, postoyannie (steadfast) is a virtue.The above paragraph suggests that Klubnikin did not believe Rudomyotkin would return nor that all must soon return to Russia to meet him and Christ on Mt. Ararat. This indicates that Maksimisty have different beliefs than Klubnikinisty who remained in this foreign metropolis.

Mexico Colonies

During the long reign of [Mexico President] Porfirio Diaz ... (1877-1910), the Mexican government encouraged the establishment of communal settlements for natives and immigrants. Some 60 colonies were started, 44 by private initiative and 16 by the government. Settlements from the United States formed 21 communities, the 10 listed* and the 11 by Mormon schismatics (Pitzer, Donald E., ed. America's Communal Utopias, Univ. of North Carolina Press, 1997, page 475)

* The list does not show the Guadalupe colony, perhaps because it was not a true commune, perhaps missed, though on the following page 476 is listed "Molokan Community (1911-?); Glendale, Arizona," which was 3 miles west of Glendale.

Before such a colony was established in the United States, agents for a large tract of land in Lower California, Mexico, learning of the immigrants'

Plans for Spiritual Christian colonies in Mexico were first considered about 1900 due to inquiries by mail and scouts. The most complete history, with many errors and omissions, appears in Mohoff, George. The Russian Colony of Guadalupe Molokans in Mexico, self-published, 1995. Many errors and omissions in Mohoff's book will be corrected later. Mainly Pryguny colonized Mexico. More information with maps. Below I refer to Mohoff's book as "Mohoff."

This tract of land consisting of 13,000 acres [20.3 square miles] was located 60 miles south of the United States-Mexico border, in a pretty valley through which flowed a small stream but which turned into a torrent after a rain storm. The land was capable of producing a good crop of wheat in a rainy year but was also subjected to cycles of dry years in the same manner as other sections of California.

In any case, 50 families were attracted to the proposition to purchase the tract. Led by Vasili Gavrilitch Pivovaroff and Ivan G. Samarin the land was bought for the sum of $48,000

Mohoff (page 15) reports: "The land was leased in November 1905 and ultimately purchased from Donald Barker on Feb. 27, 1907." I believe (with no direct proof yet) that Los Angeles attorney and investor Donald Barker acted as a broker, not a "seller," and offered a deal that the immigrants could not refuse. He got them onto land with supplies for no, or little, cost, and they would pay him back with wheat not cash. The land was owned by the Mexico government and sold as "public land" at $2/ acre to foreign investors.

The price for Baja public land sold to foreign colonists was set by the Mexican government at $2/acre, but these colonists from Russia paid 85% more — $48,000/ 13,000 acres = $3.69/acre. Why? Because they asked for supplies (wagons, animals, building materials, food, etc), the bank has loan fees and Barker probably added his fee/commission, which added $22,000 to the actual land price.

Because Barker worked with several banks in Los Angeles and had investments in Mexico, he probably created a business entity which he owned, or was a primary owner and represented, and arranged the loan for the purchase through a bank in Los Angeles. The "down payment of $5,700" (Mohoff, page 12) could have been (a) earnest money he collected in cash, or (b) a paper amount wrapped into the loan used for bank fees and/or commissions. I favor (b) because $57,000/ 104 families = $54.80/ family for the down payment, which, at a dollar a day wages in Los Angeles, was nearly impossible to pay, and the goal was to get these immigrants out of Los Angeles as soon as possible before the next wave came in.

To collect the loan payments, Barker arranged for the new Pacifico flour mill to be built in Ensenada where each immigrant farmer, land purchaser, paid for his share as shown in Mohoff, pages 14-15.

His law partner was Senator Finch. He appears on many new corporation board of directors, including a Los Angeles bank and and a land investment company in Mexico.

Mohoff is wrong

page 9, page 15 — land bought from Donald Barker Feb 20, 1907

I say Barker's bank loaned money and he brokered the sale of land owned by Mexican government to colonists, as done for many other settlements.

Soon a colony was established which was to exist until well into the middle of the century, becoming in time a tourist attraction because of its quaint, old country appearance and atmosphere.

PAGE 41 But in founding the new community, they adhered strictly to the age-old method inherited from their forefathers. Thus, instead of each family building a homestead on his own farm for more efficient operation as is the custom in America and other countries, a central site was chosen for the entire community where a village was established.

Each individual was therefore compelled by necessity to transport his implements to his farm periodically to plow and cultivate it and harvest his crops in the summer, camping there for days at a time, coming home on weekends for a visit with his family.

A writer who visited the colony in 1928 had this to say of their farming methods: "The founding of a large village in Guadalupe Valley is indeed contrary to any practical consideration and is to be explained only by the existence of an old inherited juristic notion, too deeply rooted in the minds of those peasants to yield before any environmental influence. Distance from the fields were largely such that men were unable to return to their homes in the evenings but often camped on their lots for weeks. Inconvenient conditions such as are typical for Southern Russia are thus repeated where they could be easily avoided. [Footnote: Oscar Schmieder in "The Russian Colony of Guadalupe Valley" as quoted from the "Pilgrims of Russian Town," page 253.

It is true that the method was inconvenient and inefficient, but the writer failed to perceive that it satisfied the colonist's hunger for companionship and spiritual sustenance in a strange land amid surroundings inimical to preservation of the brotherhood. It is to be noted that in 1911, when a Maksimist

There were other examples of extreme allegiance to the methods of the forefathers which are rather astounding from the American perspective: PAGE 42

- The title to the whole tract of land was vested in the names of three trustees.

- No grant deeds or other evidence of ownership were issued to the individual owners. The names of individual owners were simply recorded in a community book, which was entrusted to a person elected for that purpose.

- A government surveyor never officially surveyed the land nor was the subdivision recorded in government archives. Apparently, to save the cost of a qualified surveyor, they chose the method that was used by their fathers and forefathers in Russia. Measuring off a length of rope and using natural and artificial markers, such as large embedded rocks or trees, they did the job in their own crude manner and proceeded to allot the land to the individual owners.

Each section of tillable land was then subdivided into ten parcels for which the ten family units proceeded to draw lots for their share of each category. The family units then drew lots for ownership of their individual parcels according to the need of each family. Some were dissatisfied with the quality of the land they randomly got and left.

This method was ingenious but crude, yet the amazing fact remains that, although forms changed ownership through sale and/or inheritance, the markers remained inviolate and despite the absence of deeds and of embedded surveyor's markers, never in the history of the colony were there any litigation to decide tide to a property notwithstanding the fact that there were PAGE 43 abundant seed for sowing not only law suits but bloodshed as well. One must marvel at the innate honesty of those illiterate peasants that knew God.

However, the passing of a half a century showed that this method was not only naive but careless as well as dangerous, causing much anguish and worry to the heirs of the original colonists, for their sons and grandsons eventually had to struggle to prove ownership of the land when in 1952 squatters from the city of Mexicali, discovering that no deeds were recorded to some of the colonist's land, forcibly settled upon the land and despite the intervention of Federal, troops, at times successfully claimed ownership thereto through squatters rights.

This proved to be the straw that broke the back of the first and most successful Spiritual Christian Molokan attempt at farm colonization in America. After these raids of squatters (Spanish: paracadistas) all but a very few families emigrated to the United States, and the colony as such ceased to exist.

Economics was much more significant than squatters. These Russian colonists either sold their land cheap or voluntarily abandoned land they legally owned to move to California. Ironically, many of these Spiritual Christians left Russia to avoid war taxes and a revolutionary recession, and moved to Mexico to another civil war with taxes. While these Russians got settled in Mexico, those remaining in Russia got religious freedom and less taxes, which lessened their desire to flee from Russia. The Mexican Revolution began in 1910, and war taxes were levied which raised costs for importing farm equipment and exporting wheat.

In January 1916, a group of 120 people, most from Tyukma village, Kars oblast, were the first to leave Mexico as a group. They were directed by tycoons in Southern California to farm 3000 acres near Jerome Junction, Chino Valley, Yavapai County, Arizona. In Mexico they were the Tyukma congregation, but in America they were called Dzheromskyi. (Jeromskyi) Within 8 months they did not get irrigation water as promised and abandoned Yavapai County. All sued the land company. Some went back to Mexico, a few to Los Angeles. The majority resettled at the north end of 3 other Spiritual Christian colonies, 2 miles west of the town of Glendale, Arizona, 13 miles north-west of Phoenix. Within 5 years most left Arizona in the 1920s to California.

In 1938, a smaller group began moving from Mexico to Ramona, north San Diego county. The bigger exodus to the U.S. began after WWII when the Russian-Mexican youth realized that wages were much higher in the U.S. George Mohoff explained that a friend, who moved to Los Angeles a year earlier, drove back to to visit Guadalupe in his own car. When he told his buddies that the car was his, no one believed him. In the 1990s, Mohoff exclaimed something like: "None of us could ever earn that much money in our lifetime working in Mexico! That's why I think most really left for L.A. It was not for the squatters, it was for the dollar!"

Hawaii Colony

Another most interesting episode in the Spiritual Christian Molokan quest for land occurred 10 days after

The proposition was sufficiently attractive for the people to send a delegation to explore the possibility of establishing a colony. Upon their return, however, the delegation, composed of Captain P.A. Demens, Philip M. Shubin and Mihail Step. Slivkoff, was in complete disagreement, Shubin strongly opposed the proposition while Slivkoff urged a favorable response. John Kurbatoff led the Molokan Settlement Association.

After signing the contract in Hawaii, Shubin stayed state-side to survey land in Texas, which he rejected. For the next 5 years he and others extensively toured the U.S. and Mexico at the expense of the railroads, looking for a better deal than the slums of Los Angeles, most returning to their "kingdom in the city."

The upshot of it all was that 20 families and ten men whose families were still in Russia 110 people, including about 34 real Molokane, agreed to the terms and sailed for these islands with high hopes. At this point in the episode there are different versions from different people. Some insist PAGE 44 that the would-be colonists were deceived into thinking that they were signing a contract to purchase land when, in fact they were signing a contract to work for the plantation for a number of years.

The following account is paraphrased from an article written in 1955 by Yacov Fetisoff and published in San Francisco in the same year by the Molokan Postoyannaye Community. [Footnote: The account of 50th Anniversary of The Molokan Postoyannaye Life In America, page 167.*] Being one of the would-be colonists, he relates that, among other terms, the company agreed to provide the fare from Russia to the Islands for the families of those ten whose families were still in Russia and to bring them to the Islands not later than June 1, 1906. In addition to the ten families, the company agreed to bring in 100 other families from Russia by that date and at no cost to the immigrants. The names and addresses of these potential immigrants were given to the company and the prospective colonists were notified by their friends on the island to be prepared to join them by June 1, 1906.

* Citation: "Когда и как поселились в Сан-Франсиско, Калиф., духовные христиане-молокане," Отчет духовных христиан молокан (постоянных) по поводу 150-ти летнего юбилея самостоятельного их религиозного существования со дня опубликования Высочайшего указа Государя Российского престола Александра Павловича от 22-го июля 1805 года и 50-летнего юбилея со дня переселения наших духовных христиан молокан постоянных из России в Соед. Штаты Америки, состоявшегося 22-23 и 24-го июля 1955 года в городе Сан-Франциско, Калифорния. c. 167. ("When and how Spiritual Christian Molokans settled in San Francisco," Report of Spiritual Christian Molokans (constants) over the 150th year anniversary of their independent religious existence from the date of publication of the decree of the Supreme Sovereign of the Russian tsar Alexander Pavlovich from 22th July 1805 and the 50th Anniversary of the relocation of our Spiritual Christian Molokans constants from Russia in the United States, held on 22-24 July, 1955 in San Francisco, California. Page 167)But the company stalled and by various means delayed sending the passage tickets to those families until the agreed date. They then notified the would-be colonists that they failed to live up to the agreement, and that the agreement to bring the other 100 families is null and void but they could remain there as laborers if they wanted to.

The colonists would not agree to this and gradually

Spiritual Christians were treated fair and honest by the government and plantation owners of Hawaii. Had they stayed in Hawaii and waited a year for their homesteads, they would have lived in rural isolation and today the ocean-view land of each family would be worth many millions of dollars. During their short stay, 3 leaders opposed each other, their congregants became impatient, and many preferred the easier life they had in the slums of Los Angeles. Here's some of the rest of their forgotten oral history.

When sugar prices increased more than five-fold during the American Civil War, Hawaiian plantation tycoons searched the world for cheap labor to profit from the lucrative demand. Before 1900, one tycoon went to Russia to personally petition Tolstoy to send all the Doukhobors to Hawaii, but their arrangements for Canada had been finalized by the Friends Service Committee, London. Though Dr. T. Kryshtofovich, a Russian agricultural professor and neighbor to Demens, had already advised Tolstoy that Hawaii would be too tropical for Russian peasants, the tycoons in Hawaii knew that other Russian peasants may come to California.

Before I. G. Samarin and de Blumenthal signed a land contract in Mexico on September 2, 1905, Spiritual Christians in Los Angeles were already solicited by tycoons to move to Hawaii along with all wanting to come from the Southern Caucasus. This would solve two problems: (1) remove a huge burden from Los Angeles city services and (2) provide needed white labor in Hawaii. On September 12, 1905, Captain P.A. Demens left for Hawaii to scout for these Spiritual Christians anxious to get their own farm colony. Demens' report in Los Angeles resulted in a list of 124 (65 families) households (496 people) willing to colonize in Hawaii, more than those planing to live in Mexico.

In November 1905, Demens returned to Hawaii with F. M. Shubin and M. Slivkoff for a week of negotiating with the governor for clusters of homestead farms. The two Prygun representatives wanted land for 5000 settlers, most to come directly from the Southern Caucasus. They returned to Los Angeles and after weeks of discussions, signed a contract in January 1906. Within a month, 110 Spiritual Christians boarded a boat, less than a fourth who signed up, for a free ride to their new land. No reason is know why the majority who signed up, did not go at the last minute, because an entire ship was about to be rented for all who signed up. 1,500 were at the dock to see them leave. If they did not like it, they could come back at no cost. The Molokan congregation was led by John Kurbatoff, who had a camera and 2 photos of his group showing of about 34 members have been found. The Prygun groups were led by Mike Slivkoff, who was often opposed by at least one other man, of which no group photo has been found.

During the trip, a child died and was buried at sea. In the afternoon of February 19, 1906, they arrived in Honolulu where local evangelic churches arranged a large dinner reception and guest seats at the annual Honolulu Rose Festival parade, but they would did not leave the ship. The governor boarded the ship with 2 government Russian-speakers to greet them and wish them well. One translator was assigned to see them get settled during their first week. They proceeded directly to the northeast coast of Kauai by evening, got a welcoming dinner and a train ride south to the Makee Sugar Plantation, north of Kapaa at Kealia Beach. Upon arriving, their hosts found their shacks were vandalized by the vacated Japanese workers who protested their own eviction and forced job changes.

The colonists immediately demanded and got many supplies, food, bricks for ovens, and divided into their 2 main religions, and the Pryguny had 2 conflicting leaders. The parents of the lost child wanted to go back. Upon learning they were expected to cut sugar cane their first year, most refused to work for $29 per month (generous for labor at the time). One man demanded $3.50 per day, the same wage he got in California doing skilled factory work. On April 18, 1906, the San Francisco earthquake occurred, one month after their arrival.

Their homestead land and papers could not be prepared for months, per U.S. regulations, and most wanted to buy communal land cheap rather than wait for free homesteads. All did not want to live together and seemed to have divided into 3 faiths. Different plantations were scouted. The tropical weather and insects were uncomfortable. Soon most wanted to return to Los Angeles. Some were given jobs in Honolulu loading ships, others got work on other plantations on other islands or building a dam on Oahu. Within 5 months most had abandoned Hawaii. Slivkoff was the most persistent and disappointed, and the last one to leave on August 1, 1906.

On the way back by boat to San Francisco then train to Los Angeles, most Molokane and some Pryguny chose to stay in San Francisco. The first to arrive were taken by wagon from the docks directly to the eastern side of Potrero Hill where a refugee tent camp was built by the Army, one of 26 camps. Some men got jobs from the steamship company that brought them from Hawaii, others found work repairing earthquake damage or work in the nearby steel mill and sugar factory. Most Molokane in Los Angeles joined relatives and friends in San Francisco. Some moved to farms 30-50 miles eastward in the delta, close enough to bus in to San Francisco to attend a special sobraniya over a weekend, while many met house to house. Many who remained in "The City" built or bought homes on "The Hill" and established 2 congregations, one for each faith.

The main Molokan prayer hall in America was built in San Francisco on Potrero Hill in 1929, with a friendly Prygun congregation one block away. 50 miles NE rural Molokane met house-to-house near Vacaville. Later, a second Molokan prayer hall was built east of Sheridan (120 miles NE from San Francisco, 40 miles north of Sacramento). Due to the large number of immigrants on Potrero Hill, a local Christian women's club built a settlement house on top of the hill in the midst of prayer halls of 4 non-Orthodox (Spiritual Christian) faiths from Russia (Baptist, Evangelic, Molokan, Prygun).

To aid local immigrants, the Pastor of Olivet Presbyterian Church at the NE edge of the hill ( 400 Missouri Street at 19th), opened his home and began offering English classes for men in 1908. His work was similar to that of Dr. Rev. Barlett in Los Angeles, though initially on a smaller scale, but with better management the project grew and continues today. More classes were formed for women and youth of all nationalities. In 1918, it was incorporated as the "Neighborhood House" under the California Synodical Society of Home Missions, an organization of Presbyterian Church women. In 1919, renowned architect Julia Morgan designed a permanent neighborhood house at 953 De Haro Street. On June 11, 1922, the Potrero Hill Neighborhood House was completed, mantled in beautiful wood shingle and brick, with many broad windows and balconies providing a panoramic view of San Francisco. A gymnasium was added soon thereafter where Molokane and Pryguny hosted basketball games with Dukhizhziniki from Los Angles in the 1950s.

In contrast to Spiritual Christians from Russia in Los Angeles who lost their Bethlehem Institutes in 1914 and were forced to move from The Flats(s) by urban renewal and highway building, many families on Potrero Hill remained in place much longer. The Molokan prayer hall never moved, but the Prygun meeting house closed in the early 1960s when the man who loaned the house died and his children sold it to divide their inheritance.

Much more history to be posted about the real "Molokans in America."

Medicine

PAGE 45 But while these attempts at colonization were occupying the minds of the elders, the people in general were busy with their problems of making a living, of bearing of children, arranging marriages, healing the sick and burying the dead.

The age-old habit of healing the sick without the services of a doctor continued in the midst of an abundance of doctors. The services of their own "lekar" [doctor : лекарь ], that it, old man or woman skilled in reciting appropriate prayers for any given disease, were thought to be sufficient for any occasion. Doctors were called only in the last extremity. It was not until the second generation Molokans had their own families, that the services of doctors became general.

In the matter of births too, it was thought that the services of a doctor was needless and "high falutin'". As long as several well-known and experienced midwives were available just a short block away, why not use them? It was a financial saving too.

The use of these "babkas" (elderly women) in place of doctors was not entirely abandoned until the 1920's when the city health authorities insisted that the midwives be licensed to practice, and that they learn to write in order to be able to sign the birth certificates as required by law. Being too old to learn to write, they had to give up the practice but as long as they were able to do so they unselfishly performed their functions at all hours of the day and night, more often than not, without remuneration.

Previous to this insistence of registering births, none were registered; causing many persons thus unregistered needless complications in securing their birth certificates when the need for them became a necessity to get a job during the Second World War.

This disregard or ignorance of the city and state laws in the matter of vital statistics existed also in performing marriages. It was not until ten years or more after coming to America that PAGE 46 the required marriage licenses became general at Prygun Molokan weddings after huge hearings and several court orders.

But, the weddings themselves were very joyful occasions. After all the arrangements were made (at this time-1912—the boy and the girt had a lot more to say about their future mates than when they first came here) the trousseau prepared and guests invited, came the day of the wedding. To begin the ceremony the whole congregation as well as the relatives and friends of the groom marched, singing in a procession in the middle of the street from the groom's house to the home of the bride where part of the ceremony was performed. After this the whole congregation, augmented now by the relatives of the bride, reformed the procession for the return march to the place where the ceremony was to be completed. Since no church building of that time was large enough to accommodate such a large gathering, it was frequently held in a tent temporarily erected on the back yard of the groom's father or on the lot of a friend or neighbor whose lot was roomy enough.

After the ceremony was completed the newlyweds, together with their invited friends, were seated in some large room adjacent to the tent but separated from the congregation. There they enjoyed their wedding dinner together with their invited boy and girl friends, singing songs of their own choosing and enjoying themselves in the traditional manner of young people, while the congregation was enjoying their own dinner in the tent.

The practice of marching in procession back and forth, sometimes as far away as the Vignes Street area across the bridge to Utah Street area, continued until the police authorities decided that, because of increasing street traffic, it was becoming dangerous. They therefore requested the elders to discontinue the practice and some time around 1915 the wedding processions were abandoned except for the necessary relatives and friends who henceforth accompanied the groom to the bride's PAGE 47 house and from the bride's house directly to the site of the marriage ceremony.

Of course the use of the automobiles did not become general

until the middle of the 1920's when the Molokan population

scattered from the Flats to the various parts of east and south

Los Angeles.

Funerals Also see Cemetery, Chapter 7

The funerals on the other hand, presented their own problems. These were solved in the characteristic old Russia Molokan fashion. Unlike present day funerals when all arrangements are left to the undertakers, all work was done and all arrangements were made by the family or by their relatives and friends as they did in Russia.

Immediately upon the death of a person, the members of the family bathed the body. If the deceased had been sick for a while before death, all necessary clothing would have been prepared before hand and the body would be dressed there and then in the new apparel and laid out on benches in the front room of the deceased's home. Meanwhile, friends and relatives of the family skilled at carpentry would build a plain, unadorned, redwood casket. A grave marker of 3x8 red wood plank 8-ft. long would also be prepared. This would be hand-carved with the necessary data prescribed by old Russia Molokan customs

Other friends would see to securing a burial permit and to ordering a funeral car from the local streetcar company. They would also order two or three regular streetcars to accommodate the people for the trip to the cemetery.

But if the death was sudden, women friends would drop their daily chores to sew the needed garments so that the body could be bathed and dressed as soon as possible and Placed in the front room to be viewed and wept over. On the morning of the funeral the body would be placed in the casket and everything was ready for the funeral.

When the moment arrived for the funeral, the body was carried out to the middle of the street where a rug was spread out. A cloth-covered table was placed in the proper position PAGE 48 and the casket was placed on benches near the foot of the table while the proper hymn was sung for the rise and resurrection of the deceased. After the usual prayers were recited, the body accompanied by the singing congregation and the weeping relatives and friends, was carried to the nearest streetcar stop.

The casket would then be placed in the funeral car which would also have room for the relatives while the rest of the people would crowd into the specially ordered cars and, following the hearse, would proceed to the place of interment.

During the first five years in

Los Angeles the interment took place in the Los Angeles County

cemetery-for-the-indigent [called "Potters field"] which

was located (and still is*)

adjacent to the Evergreen Cemetery on East First St. But by 1909

the Molokan population increased to such an extent that there

was much grumbling among the younger Maksimisty-Pryguny people

that our dead deserved a better fate than to be buried among the

county's indigent and undesirable elements**

and that the Spiritual Christians Molokans

were now numerous enough to afford a cemetery of their own.

Consequently they began to agitate for the purchase of a site

for a private cemetery.

* In 1964, five years before Berokoff published his book, the County sold 6 of its 10 acres to Evergreen Cemetery and maintained about 4 acres with the crematorium.

** Most likely because they were being buried among pork-eaters and pondering this Bible passage from Matthew 27:7-10: "And after they had consulted together, they bought with them the potter's field [Russian: землею горшечника], to be a burying place for strangers. ... And they gave them unto the potter's field [Russian: землю крови : field of blood], as the Lord appointed to me." (Douay-Rheims Bible: Matthew 27:7-10)

But the urge to leave the city was so great that there was a

strong opposition on the part of the older generation who argued

that the Maksimisty] Molokans

were not going to remain in the city very long, therefore a

private cemetery was not needed. Despite this opposition a

half-acre site was purchased in 1909 on East

Second St. near Eastern Ave. This part of the city was

then an unpopulated barley field nearly a mile from the nearest

streetcar line. It was at the terminus of the Whittier Blvd. car

line near the intersection of Eastern Ave and

up a steep unpaved road, which was often muddy.

In 1909 Orthodox Serbian immigrants had

bought a large tract of land east of Los Angeles for their Saint

Sava Serbian Orthodox Church of Los Angeles and

cemetery. Many of the younger Serbs thought they had too much

land and offered some to their Russian Spiritual Christian

acquaintances for their own cemetery. The Slavs and Russians

were often confused by outsiders, and the press. They all

spoke Slavic languages, were classmates (English, citizenship,

sloyd) and worked together (factories, lumber, railway). By

the 1950s, the Church members wished they did not sell because

they needed a larger church which they built in San Gabriel in

the early 1960s on donated land, maintaining the old Church

for smaller gatherings.

Today the leaders of S.S.S.O.C. are

disappointed that their Russian neighbors rejected a proposal

to close off and annex the adjacent streets for a larger

parking area which both could use. The unspoken likely reason

for their rejection is not that it was not a good idea which

could benefit both neighbors, but that the most zealous Dukh-i-zhizniki

believe they all will become Spiritually ne chistyi

(не чистый : unclean) because it is pohanyi (poganyi

: поганый : filthy) to have contact with pravoslavnye

(православные : Orthodox).

It's ironic that these Spiritual

Christians who complained of persecution by the Orthodox

Church in Russia and won't meet their neighbors half-way

today, accepted the generous offer 100 years ago from friendly

Orthodox Christians in the U.S. But, not all American Maksimisty supported

those in L.A. being buried in land consecrated

by a priest, adjacent to Orthodox especially with bodies

traditionally buried facing East, directly at an Orthodox

cross. It is also a shame that they would not cooperate with

the parking lot proposal.

As soon as the site was purchased and fenced, permission was

secured from the County to remove all those bodies that were

buried in the County cemetery to the new location. In January and February 1910, 85 of 150

Russian Spiritual Christian graves (57%) Approximately

twenty or thirty bodies were

disinterred and PAGE 49

moved to the new site within a week with all due religious

ceremony and emotional expression from the bereaved families who

took advantage of the occasion to view their loved ones for

another and the last time.

For over a century, 65 Spiritual

Christians, born in Russia and

babies just-born in the US,

remain buried in unmarked graves along Lorena street under the

east end of Evergreen Cemetery. In 1910 they were left behind

in the former hillside "Potters Field," the Historic

Los Angeles Cemetery. In 1964, Evergreen Cemetery bought

most of this sloped land to expand, which was leveled with

fill dirt to sell graves on top of those buried 50+ years

earlier. A common grave marker for these forgotten souls from Russian

should be properly placed there as the Chinese did for their

people in 2010.

Although the distance from the end of the street car line to

the new cemetery was very long and up a

steep unpaved road, it did not deter the Spiritual Christians Molokans

from performing the full rites for the deceased as well as to

pay their last respects to them. The body was always carried the

full distance by relays of pallbearers, followed by the full

congregation singing the appropriate hymn the meanwhile. This

custom prevailed for a period of 12 years or until the early