In 1980 Gwyn Jolly wrote as part of a college assignment a biography of her grandmother Marie Bestwick (born Akulyna Shubin). These first two chapters of that biography may be of interest to those who would like to know something of the life of the Molokan people in Russia and also what is was like to enter America through Ellis Island. -- submitted by her father, John Jolly

Also see Biography of Elsie Shubin, Marie's sister Parasha.

Marie N. Shubin-Bestwick:

A biography by her grand-daughter Gwyn Jolly

Chapter 1 -- 2 -- 3

The Russian Village

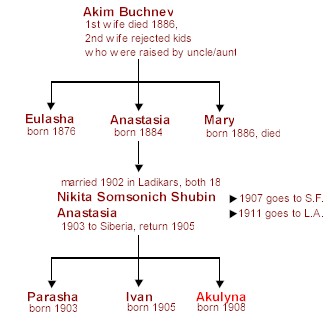

On September 15,1884, Anastasia Akimovna Buchnev was born in the small Russian village of Selim. Selim was located in the Turkish province of Kars which was at this time occupied by the Russians. [See lower left of Kars map.]

The village had only one street which was two miles long with farmhouses on each side of it. The only places of business in Selim were a notions’ store, a cobblers bench, and a dairy run by an Armenian. There was also a Molokan church which was located in the center of the village.

In 1886, Anastasia’s mother died. The father remarried but his new wife would not accept her new stepchildren. Anastasia, her eight year old sister Eulasha and her six month old sister Mary went to live with their aunt and uncle and their five children. Eulasha and Anastasia survived but little Mary died of starvation.

Anastasia wanted to learn to read, but education was not allowed for the girls. Her male cousins were sent to school and at night Anastasia would secretly study. She was caught studying several times and as punishment she was beaten. But Anastasia continued to study and was able to teach herself to read by studying the Russian bible.

In September of 1902 Anastasia married Nikita Somsonich Shubin, an eighteen year old orphan from the nearby village of Ladikars. The wedding took place in the village. Anastasia was dressed in her wedding clothes with a shawl wrapped around her head to symbolize the Virgin Mary. Because of the shawl, she could not see at all, and she had to be led to the church steps by her friends and family. There she met Nikita and his friends. After the wedding ceremony was performed, the village had the traditional feast of borshch [soup], meat, and a watery sauce of raisins and prunes for dessert [Russian kompot, boiled dried fruit].

One year later, Anastasia had her first baby. Nikita and Anastasia named the girl Parasha. [See Biography of Elsie Shubin] At the same time, Nikita heard of opportunities in homesteading in Siberia. In late 1903, Anastasia, Nikita and the new baby moved to Siberia.

There, life was very difficult for them. There were no cows and so Anastasia and Parasha had to drink mare’s milk. The other settlers in their area were Mongolians and they had very different customs. These people would build tents and huts from animal skins and they spoke a different language. Because Anastasia was raised in the adobe houses of Selim, she tried to improvise and she built an adobe igloo, which she had to crawl through one small opening to enter. During the day, Anastasia worked with Nikita and the other men in the fields.

In 1905 a member of the nobility gave birth to a son, and in celebration all Russians were given free passage on trains. Nikita and Anastasia decided to take advantage of this opportunity and return to Selim. The journey should have lasted eleven days, but instead it lasted a month because the trains were put off the tracks due to the Russian-Japanese war.

It was 1905 when they returned to Selim. Anastasia soon gave birth to a son whom they named Ivan. For the next two years Nikita worked at a wheat mill. They lived in a small two room adobe hut which was located behind the notions store. The notions store was run by Anastasia’s uncle.

One room of this hut was a kitchen. The other room was the family room. The two rooms were separated by the stove. During the winter, the children slept on the stove to stay warm. The family room had a table and benches , but no individual chairs or stools. The bed consisted of a homemade wooden frame with wood slats. There were not mattresses but homemade rag rugs were use as padding. The rag rugs were also used as sheets. The pillows and quilts were stuffed with goose and duck feathers and the comforters were made of wool. Although primitive, the bed was warm and comfortable to sleep on.

Not all people in Selim lived in adobe houses. The ones who were better off financially had frame houses with wooden floors. But Nikita and Anastasia were one of the poorer couples. To keep the dirt floor smooth and shiny, Anastasia would mix horse and cow manure with water and then spread it across the floor. After this treatment the floor would be as smooth as linoleum.

Every morning Anastasia would take Parasha outside and they would go to the well to draw their day’s supply of water. At the well all the women of the village would gather and discuss any news or rumors that they had heard. The persistent rumor was that there was an upcoming war with Germany and that the men of Selim were in danger of being drafted. Nikita decided that it would be better to emigrate to America and to take his chances there, then to face the risk of being drafted and killed. He received his passport in June of 1907. In the Fall of that year, he left for America. On the way to America, Nikita met a woman with two children. She was having problems because she did not have the correct papers for emigration. Nikita decided to help the woman out and he explained to the official that they were his wife and children. As ‘proof’ he showed the official the information about his family that was written on his passport.

In late 1907, Nikita arrived in America. He got a job in the shipyards of San Francisco for a dollar a day. [Some from Selim were in S.F., and others from Selim built a village near Ukiah, along the Russian River in Potter Valley.] He managed to save enough money from this job to sent Anastasia seventy-five dollars. For the next four years Anastasia struggled to feed the children and earn the remaining amount of money to make up the necessary four hundred dollars for her and the children to emigrate.

On July 12, 1908 Anastasia had a daughter whom she named Akulyna. While Anastasia would work, young Parasha would baby sit Ivan and Akulyna. Anastasia would leave before dawn and she would not return until sometimes after midnight. She would work all day in the fields and her pay was milk, bread, eggs, and buttermilk. During the harvest even the small children were expected to assist with the work in the fields. The main crops in the fields were wheat and barley. Individual households would grow their own crops in the gardens such as peas, potatoes, carrots, beets, turnips, and sunflowers. For entertainment on Summer evenings the adults would gather with their friends in front of their homes, talking and eating sunflower seeds.

The people of Selim would supplement their diet by bartering with the traders from Turkey who would occasionally pass through their village. They would drive through in caravans with donkeys carrying their wares. These traders would bring cabbage (the villagers would live on sauerkraut during the winters), cherries, grapes, the apples and pears were bought mainly to sweeten up the smell of the houses.

During the Summers as Anastasia and her friends would be walking and eating sunflower seeds, Parasha would go swimming in the lake. At night the adults would tell fairy tales to each other. Most people in Selim were illiterate, so when someone read a story they would make it part of their personal story. As the horror stories were being told about goblins, witches, and werewolves, the storyteller would emphasize, “And my cousin was there!” or “It chased my mother”.

During the Winters, the women would gather manure to burn for fuel. Parasha and Ivan would run outside and play barefoot on the snow and ice. The children of the wealthier families would be bundled up warmly and stay inside. But because they were so over-protected, when they would play outside they would often catch pneumonia and die.

Also during the Winters, the Russian soldiers would be on maneuvers near Selim. They would ride through the village on horseback, wearing their fur overcoats. By law the villagers were required to quarter the soldiers in their homes. The soldiers would sleep on the floor and they would bring their own food. The soldiers would eat a black type of bread which was so hard crusted that the soldiers had to split it open with their hatchets.

Parasha, Ivan, and Akulyna would listen as their soldier-guests would tell stories and sing songs late into the evening.

One day when Parasha was three years old, she was walking down the road with her mother. They were both getting tired, so when a man passed by with a cart full of beets, Anastasia asked if Parasha could ride in the back. But after Parasha had sat in the cart, the horse spooked and galloped off with Parasha being tossed around in the cart with all the rocks. When the man and Anastasia finally caught up with them, Parasha was unable to speak.

When Parasha still had not spoken after several hours, a worried Anastasia took Parasha to the home of one of the healing grandmothers in Selim. These women were addressed as ‘Babunya’ [old woman, granny] and they practiced a type of spiritualism. They were very religious and they knew how to heal by prayer. The woman healed Parasha and then she spoke to Anastasia.

She said, “I won’t always be around to help you, so I’ll teach you how to heal.” And the babunya taught Anastasia how to heal by prayer.

Chapter 2 -- 1 -- 3

The Trip to America

By 1911 Anastasia felt that she was ready to join Nikita in America. Parasha was eight, Ivan was five, and Akulyna was three years old. Anastasia sold the cow and calf, any furniture that she did not plan to take with her, and the hay in the yard to earn the rest of the money for the trip. About a hundred people from the village left with Anastasia and her children, and most of these people were related to Anastasia in some way. [Bogdanoff, Fetisoff, Kanihin, Konovaloff, Loskutoff, Papin, Susoeff, ...]

Anastasia’s first major complication occurred when she applied for her passport. The official showed her how Nikita had already left Russia with his wife and children! Anastasia knew nothing about Nikita helping the woman and her children that he met on his trip, so she turned to her uncle for help. The uncle spoke with the official for a short time and then he gave the official fifteen pounds of cheese and ten pounds of butter. After that Anastasia had no problem getting her papers in order.

The group left in February, with each family group in a sled, keeping warm by snuggling under the feather bedding. After traveling all day by sled, a worried Parasha asked her mother if she was sure that they hadn’t already passed America.

After they sledded for a full day heading North-East, the reached the fortress city of Kars. Kars was the nearest city in the border area and it had a train station. There they boarded a train which took them North-West to Bremen, Germany. At every train stop, Anastasia would get out and look around while Parasha waited with Ivan and Akulyna. She was terrified that Anastasia would be left behind and she would have to continue the trip without her mother.

At one stop, Parasha went exploring with another little girl. Parasha forgot to hold the door open and the train door cut off the little girl’s thumb. Years later, when the girl married Ivan, friends joked that Parasha had marked her as a sister-in-law on the train. Finally they arrived at Bremen [Germany], the major port city in Europe for people trying to emigrate to America.

At Bremen, Anastasia was faced with a new complication. She was told that she needed sixty more dollars to complete the trip. Anastasia had spent all the money already just to leave Russia, and she knew that no one else had the money to lend her. As she stood in the station crying, a man dressed as a pauper asked what was wrong. She told him her situation and he told her that he only dressed so poorly so that people would not ask him for money. He gave her sixty dollars and she was able to continue the trip with her children.

Before they could leave Bremen, the group was kept in quarantine until the officials were satisfied that the people were not carrying any contagious diseases. Then they were allowed to board the ship for the final leg of their journey.

On the ship, the people of Selim kept together, and they lived on a strict diet of melba toast [dried bread, sukhori], corn beef, and boiled potatoes. The ship was equipped with enough food to feed these people but because they were of the Molokan religion, the people of Selim followed the Kosher dietary laws of the Bible. Each family had prepared enough food before the journey to make sure that the food was up to the standard that they required. They kept the food in crock jars sealed with fat. Since it was winter time, the food did not spoil on the voyage. Some young men helped Anastasia with the baggage and looking after the children. In exchange, Anastasia shared her food with these men.

For entertainment, the sailors would call out to the children that there were mermaids swimming behind the ship. Parasha and her friends would race to the end of the ship trying to catch a glimpse of them. At night, Parasha would keep busy by telling the other children all the fairy and horror stories that she had heard back in Selim.

Finally the ship reached Ellis Island. There was a great amount of fear among the adults at this point, because they knew that they could still be sent back if they did not pass the tests there. The fear was even communicated to the children waiting to be processed. One of those who failed to pass the tests was Mary Bogdonov, one of Anastasia’s cousins. The American officials decided that she was mentally ill. Her husband and children were allowed to enter, but Mary was sent back. Fortunately for Mary, she was able to pass the tests the following year.

At Ellis Island, Anastasia faced a third complication. She was not allowed to leave the island until she proved to the American officials that she had twenty-five dollars. She knew that Nikita was living in Los Angeles at the time, so she sent a telegram to the Russian community there, explaining that her last name was Shubin and that she and her three children needed twenty-five dollars to get off Ellis Island.

Another Shubin there thought this was his own family and he sent the money. From New York to Los Angeles the family traveled by train. they went through the deep South where they saw Blacks for the first time. Finally they arrived in Los Angeles in mid-March.

Nikita met his family at the train station. After four years of separation Parasha, Ivan, and especially Akulyna did not recognize their own father. Nikita was working in the lumber yard in San Pedro by this time and he took them to stay that night at a friend’s house.

As the family came towards the house, someone inside started playing the phonograph as a welcome. None of the newly arrived Russians had ever seen a phonograph before and that evening Parasha and Ivan tried to take the machine apart to find the tiny musicians.

Anastasia handed Nikita the twenty-five dollars that she had kept since Ellis Island. Nikita spent it in one night happily celebrating with his friends. When he next took his family to one of the regular meeting of the Russian community in Los Angeles, a man stood up and asked, “What man named Shubin is expecting a wife and three children from Russia? He owes me twenty-five dollars!” Nikita had to pay the man after sheepishly admitting that he had spent the money.

Within a month after arriving in America, Anastasia learned the Selim had been totally wiped out by a marauding group, possibly Turkish soldiers. [Actually it's still there today occupied mostly by Kurds. Anne and Rose Tolmasoff-Strubar surveyed the Kars Molokan villages in 1987.]

Chapter 3 -- 1 -- 2

Americanization

Almost immediately, the family started to become Americanized. Nikita tried very hard to learn English. He took the American name of Mike. Anastasia took the name of Nellie. A neighbor girl who became Parasha’s best friend renamed her Elsie. Ivan became John and Akulyna became Mary. The children were expected to do the shopping at the local store and within six months they learned how to speak English.

|

Mike and Nellie now had less frequent contacts with the Russian community. They still went to some meetings but they were a lot more open about accepting the new customs. Nellie was scolded by her neighbors for going against tradition because she stopped wearing a head scarf.

Their first American home, though, was in the Russian community in Boyle Heights [Flats]. They lived in a five room house at Gless Street and 1st Street. Two blocks away was the Utah Street School where Elsie and John went to school for the first time in their lives.

The other Russians would lie to school officials about their children’s ages so that the children could start school at age four instead of six. This way they could leave school at an earlier age and work to help support their families. They would also make all types of excuses for not learning to speak English. The children would be behind in school because their English was so poor.

Although Mike and Nellie saw many opportunities in the American way of life, they held onto some of the old religious traditions from Russia. For example, the dietary laws were still enforced in their home. But some American friends from school soon introduced Elsie, John and Mary to the forbidden pleasures of eating ham and bacon.

In 1913 Nellie had a son. He was named Pete. In 1914 Mike and Nellie had another daughter and they named the girl Anne. After this last birth, Nellie became seriously ill. She got worse and a doctor was called. He got there too late to save Nellie. As six year old Mary waited at the foot of the bed, the doctor handed Mike Shubin the death certificate for his wife.

While Mary did not understand what was happening, she did see the bed start to shake. At this point Nellie had the strange sensation of floating down a tunnel. At the end of the tunnel, she saw several of her dead relatives. Her father met her and told her to go back, telling her that she must not leave her children to become orphans.

Nellie recovered slowly. For the next thirteen months, she stayed at the Patton State Hospital. Because Mike was working such long hours, he farmed out his children to different families.

Elsie went to live with her new friend who had named her. John went to live with some Russians in Delano. Mary stayed with an American family and Pete stayed with a Russian family. Anne went to live with a childless Russian couple who soon moved to San Francisco.

At the hospital, Nellie impressed one of her doctors by her determination to recover. He heard her singing hymns in Russian and he told her that she was one in a thousand. He told her that she would get better and that she would leave the hospital soon.

When Nellie returned home, the children all came home too except for Anne. She was adopted by her new family but she did keep in touch with her old family until she died in 1930 at the age of sixteen.

At the Utah Street School when Mary was in the fourth grade, her teacher kept her after school one day and told her that there were three Mary Shubins in the class. To avoid confusion, the teacher asked if she could call her Marie instead. Mary was delighted to have a new name and from then on, she was known as Marie Shubin.

A year later, in 1918, Mike moved his family to San Pedro where they lived in two tent houses. One tent was used for sleeping in and the other was used as a kitchen. Mike was a strict father, but he was also affectionate. Marie looked out the window of the tent one day. She saw her parents singing happily as they were drawing water from the nearby well. As they were doing this they were hugging each other. Soon afterwards, they moved to a real house.

Mike started trying new jobs as he got more self-confident. He ran a grocery store for a while, but he was not a good businessman. He allowed the meat and other products to go at too low a price to make any profit. His next business venture was a success. Mike started a rubbish collection business with an Armenian friend.

John was in high school by this time and he would help by getting up a four o’clock every morning to help his father make the rounds. Although Mike was trying to Americanize his family, he was quite strict. Elsie quit school in ninth grade although she badly wanted to continue her education. She wanted to marry an American boy but Mike would not hear of it. Instead she ended up marrying a boy from the Russian community to please her father.

Marie was by far the most Americanized of the family born in Russia. She was the only child in the Russian Community to continue her education after she was sixteen years old. When she was in high school she joined the girl reserves and for two Summers in a row she went to camp at Solimar near Carpinteria.

Marie was quite sickly though. She wore glasses, was very thin and she had to wear orthopedic shoes. She was the only senior to graduate from San Pedro High School who did not have to take physical education. Instead she took a class in nutrition. Marie also had to wear a special garment because the doctor told her that she had a fallen stomach. He said that she could never have any children.

Marie had to walk several miles uphill to the high school every morning. Mike wanted to save her the walk, so he offered her a daily ride to school in the rubbish truck. Marie was horrified and she quickly thought of some excuse not to accept the ride. Because of her poor health, Marie graduated a year and a half behind the rest of her class due to all her absences.

When Marie was sixteen years old, she went with her father to attend a funeral. There Marie met a young Russian named Mike Dimitrov. He had no plans to continue his own education but he liked the idea of Marie going to school. He told her that when she finished her education, they would get married.

But Marie had her doubts about him. Her father had told her that if she did not marry a Russian he would disown her. But Nellie had privately told Marie, "Whatever you do, don’t marry a Russian."

One thing that Marie did not like about her new fiancé was his smug superiority. He would tease her because she did not know how to read and write in Russian. Also he was insensitive to Marie’s feelings. They went on a double date with another Russian couple to an amusement park and Mike Dimitrov told the other couple not to speak to Marie in English but to make her speak Russian. He would then make fun of her Russian.

Marie was in no hurry to finish her education so she went for a year to college. At the end of her first year she spent a day in Los Angeles. She was in Pershing Square reading the Los Angeles Times when she saw an ad for a job with Weeden’s Publishing House. She walked the few blocks to take the interview and out of fifty applicants she was the one selected.

Regarding the rest of this book, John Jolly, who submitted these first three chapters says: "Since Marie Bestwick married an Englishman and left the Molokan church, I do not think her story would have a great appeal for your readership." Thanks for what you sent, John.

Elsie (Parasha) 1903-1996 married Andrew Shubin 1901-1952.

John married Hazel ? who was also a Molokan.

Pete married Faye Tolmasoff. (Big Church on Lorena Street)

Anne did not marry and died young.

Here's how you readers can help: "Would someone who knows please fill in the missing spouses names and send them." Spasibo.