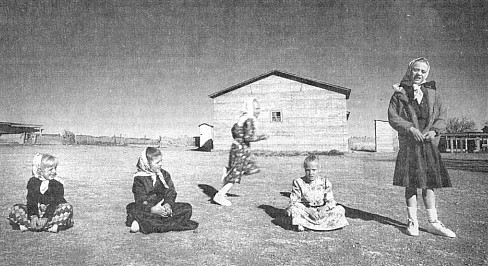

Mennonites fight off vicesIn Cuauhtemoc, Mexico, Mennonites are battling drug use among their young. February 4, 2001 —- By Julie Watson, Associated Press CUAUHTEMOC, Mexico — Every evening, Mennonite families in the plains of northern Mexico gather around their radios in stark adobe farmhouses and tune in to Blanca Peters' community newscast.

The broadcast in Low German sprinkled with Spanish gives a thorough update of Mennonite life in the area, detailing everything from how tall the corn has grown to who has fallen sick or given birth. But one night last fall, Peters left out a notable item: A police raid that netted crack cocaine and a 9mm pistol, shaking the foundations of this conservative community as it faces an increasing culture of drug dealing and addiction. Six Mennonites were arrested in the raid. "Based on their own community's comments, we're sure there are a lot more crack houses than just those two," says Enrique Villagran, Cuauhtemoc's police chief. "Their leaders are very worried about this, given their traditions, customs and highly religious, moral lifestyle." About 9,000 Mennonites moved from Canada to the desolate plains of Chihuahua state in 1922 to preserve a way of life rooted in working the land and cherishing family, God and tradition. Mexico was the last stop on a long journey to uphold their beliefs not to fight in wars, which took them from Germany to Russia to Canada. [In 1929, two conservative sectarian groups — Sons of Freedom [an early 1900s schism from Canadian Doukhobors] and Arizona Maksimisty — explored the possibility of moving their colonies to Mexico, near the Mennonites. A scouting group of Sons of Freedom from British Columbia, traveled down the west coast stopping at Molokan, Prygun and Dukh-i-zhiznik settlements on their way to find the Mennonite colonies in Mexico. When they got to Arizona, the elder Tolmachoff presbyter said that his Pryguny-Maksimisty were also interested in joining the Sons of Freedom if they decided to move to Mexico and asked that they report back. The result was no move from Canada or from Arizona. In the 1941 art book Hilltop Russians in San Francisco, artist Pauline Vinson illustrated one of the Sons of Freedom during their visit.] In Mexico, they kept to themselves for decades,

living in remote camps with names like Manitoba Colony

and valuing a simple life, much like the Amish. Few

speak Spanish. While only two decades ago, they lived

without electricity or cars, now Mexico's 50,000*

Mennonites are battling to keep the vices of modern

society at bay as stores, pickups and tractors have

seeped into their once-remote camps. [* It

is the home of around 200,000 Mennonite people

divided into various colonies that surround the

city. ] In the past decade, Mexican and U.S. authorities have arrested dozens of Mennonites for drug dealing and smuggling. Drug dealers are recruiting members from within the Mennonite churches in northern Mexico, according to the Mennonite Brethren Herald, a local bulletin. "More than 100 Mennonites are in prison for drug dealing, and that is only the tip of the iceberg," Jacob Funk, a Mennonite minister from Canada who visited the area last March, told the newspaper. "The most common problems are drugs, alcohol and marital infidelity," Funk said. "There's a real hunger for a message of hope." A year ago, police started patrolling 56 camps at the request of Mennonite leaders worried about crime, and plans are under way to open a drug rehabilitation center. U.S. Customs agents last year arrested three people with Germanic last names from Cuauhtemoc. Each was caught smuggling more than 100 pounds of marijuana into Texas. All three are believed to be Mennonites, although Customs does not ask the religion of those it arrests. Manuel Caracosa Alvarado, who runs a drug and rehabilitation center in Cuauhtemoc, says he treats an average of 100 Mennonites a year, many for addictions to hard drugs like crack cocaine and heroin. Francisco Friessen checked himself into the center after he flipped over his tractor, trapping himself beneath it. "I know a lot of people in my camp who should be getting help for their alcohol or drug addictions," the shy man says. Used to be by the time Mennonite boys could hold a pitchfork, they would work alongside their fathers from dawn to dusk on prosperous farms. But a 10-year drought has left barely enough work for even the fathers. Many who do not have more than a middle-school education and speak only the Mennonites' dialect of Low German pass the time lying in the sun-drenched fields smoking cigarettes or sneaking off to discos in nearby Cuauhtemoc. Dancing is still frowned upon by conservatives. Others have left their protected communities to work in nearby cities or in the United States and Canada, leaving them exposed to the influences that caused their grandparents to flee. "Some have lost the faith," says Cornelio Peters, a minister and father of seven, sitting in a living room with only a few chairs, a grandfather clock and a wood-burning stove. "We need more land so the young can work alongside their parents and not be running around loose." "Those who know the Bible know that evil continues to grow," Peters says. "These things will continue growing until they end the world. There is a lack of faith in God. They need to stop thinking about trafficking drugs, about taking drugs. When we were young, there weren't these influences." The minister knows it's not easy to keep out change. He and his wife adhere strictly to traditional Mennonite dress, but their sons have swapped their overalls for Levi's and T-shirts. A year ago, a conservative faction moved to the southern Mexican state of Campeche to return to a life without electricity or cars, just as their grandparents did seven decades ago. But Margarita Neufeld, 25, says her people can't run forever. "A lot of Mennonites do not want to see reality," says Neufeld, whose bobbed hair, makeup and flared pants are a sharp contrast to her mother's cotton frocks and braided hair. Neufeld, a clerk at a grocery store in the camps, wants to write a telenovela, as Mexico's popular prime-time soap operas are known, about Mennonites. "Maybe it will cause people here to face what's happening," Neufeld says. "A lot of young people like to go out to the discos because there is no place to go to have fun in the camps. There are drug addicts, lots of drug dealing, people are marrying Mexicans and if their parents don't accept it, they leave." Neufeld says her older brother is a recovering drug addict who married a non-Mennonite Mexican woman and moved to nearby Cuauhtemoc. "We want to be Mexicans. A lot of young people don't

want to live apart anymore," she says. "We know what's

out there, and we want to be a part of it." More info:

Webpages that link to this page:

|

|||||

|

Spiritual Christian NEWS Spiritual Christians Around the World |